Psychology

Psychology at Smith is consistently one of the most popular majors on campus. The department’s faculty is strongly committed to providing a rich, diverse curriculum to majors and nonmajors alike. Our mission is to develop skills that will serve students well in psychology but that can also be applied in other important arenas, including writing and communication skills, hands-on training and multicultural fluency. We emphasize student participation in research; faculty-student collaboration and mentoring; and preparation and guidance for future studies in psychology and related fields.

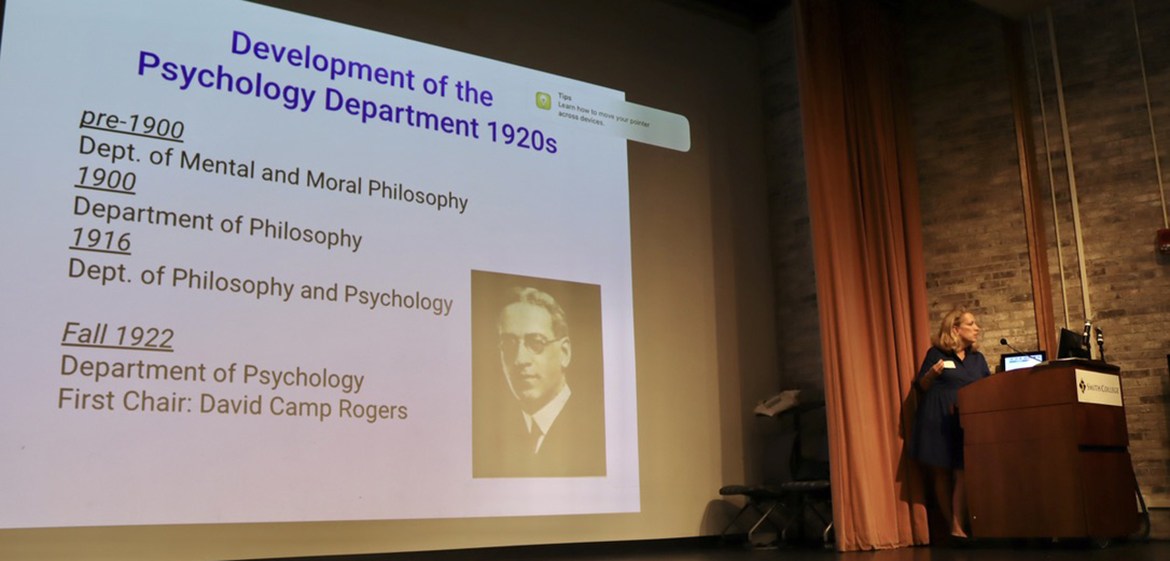

We’ve Turned 100!

In the 1922–23 academic year, the official founding of the Smith College psychology department—previously housed under the umbrella of the philosophy department—was a prescient and bold decision. We celebrated with a centennial symposium—a full day of events, lectures and discussions highlighting the pioneering efforts of Smith’s faculty, staff, students and graduates.

WATCH THE RECORDING VIEW A SLIDESHOW READ ALUM PROFILES

Announcements

Congratulations, Stephaney Perez '23!

Stephaney Perez '23 will be attending Georgetown University for the M.A. in Latin American Studies this fall. A double major in Psychology and Latin American Studies, she is the first in her family to attend graduate school and in a field about which she is deeply passionate.

Congratulations Caitlin Senni AC '23

Caitlin Senni AC '23 was awarded a GAANN fellowship to support her pursuit of a Ph.D. at the University of Connecticut.

Congratulations, Rosina Asiamah AC '23!

Rosina Asiamah, Ada Comstock Scholar '23 was awarded full funding and will be attending the University of Rochester School of Nursing one-year Accelerated Bachelor of Science in Nursing starting this fall.

Psychology department faculty affirmed the following learning goals for our majors. Students will:

- Develop a knowledge base of psychology, becoming familiar with the important theories, findings and historical perspectives in the field.

- Become critical consumers of research and learn to think critically about behavior, brain and mental processes; understand the relations among theories, observations and conclusions; and weigh evidence in evaluating particular theories or approaches.

- Develop research and quantitative fluency, including the ability to develop hypotheses, design studies, and understand, analyze and represent data.

- Develop requisite writing and communication skills within the discipline.

- Understand the ethics and philosophy of science.

- Develop multicultural fluency, including the ability to view issues from different cultural perspectives and to ask pertinent questions about cultural influences.

Each student, with the approval of their major adviser, elects course selections that meet the following requirements:

- Majors must take a minimum of 10 courses, including the foundational courses in psychology (100, 201, 202).

Basis

- PSY 100 Introduction to Psychology

- SDS 201 Statistical Methods

- PSY 202 Introduction to Research Methods

Foundational courses must be taken using the regular grading option (not S/U). Students should normally complete these foundational courses by the end of their sophomore year. Discuss requests for waivers (e.g., AP tests, transfer credits) with your adviser.

Beyond these, students are required to achieve breadth and depth across the following major curricular tracks of study:

- Mind and Brain

- Health and Illness

- Person and Society

Breadth is achieved by selecting one course within each of the department's three curricular areas. Depth is achieved by selecting at least two colloquia (psychology courses with numbers 200 or above) as well as two courses at the advanced level (300 or above), at least one of which is a seminar. Note that 200-level courses from other departments (such as EDC 238, ESS 220, EDC 239) count as psychology breadth courses but do not count as psychology colloquia. Furthermore, depth requires that at least one course at the advanced level combines with the student's other courses to create a constellation of three courses that represent a depth in a field of study that is important to the student and recognized by the department as relevant to psychology. Students may count no more than three 100-level courses toward the major, not including PSY100. Although we discourage the use of the S/U option for courses in the major, students are allowed to take nonfoundational courses S/U. All students (including transfer students) must take at least one colloquium and one advanced seminar within the department.

In particular, any student planning a career in academic or professional psychology, social work, personnel work involving guidance or counseling, psychological research or paraprofessional occupations in mental health settings or special education programs should regularly consult her major adviser regarding desirable sequencing of courses.

Finding an advisor

Students who wish to declare a psychology major should email the departmental assistant, Laura Fountain-Cincotta (lfountaincincotta@smith.edu), who will direct them to faculty who have space for advisees.

Each student, with the approval of their minor adviser, elects course selections that meet the following requirements:

- Six semester courses including two of the three courses that comprise the foundational courses for the major and four additional courses selected from at least two of the three areas. In addition, one of these four courses must be a colloquium and one must be a seminar. Note that 200-level courses from other departments (such as EDC 238, ESS 220, EDC 239) count as psychology breadth courses but do not count as psychology colloquia. All courses must be taken using the regular grading option.

Basis (only 2 of these are required):

- PSY 100 Introduction to Psychology

- SDS 201/PSY 201 Statistical Methods

- PSY 202 Introduction to Research Methods

The basis must be completed before entering the senior year. Minors must then complete no less than four additional courses from at least two of the department's three curricular tracks of study. One of these four additional courses must be a seminar.

- Mind and Brain

- Health and Illness

- Person and Society

The departmental honors thesis is for senior psychology majors interested in conducting independent research on a particular topic. Honors students work closely with a faculty member to conceptualize, design, and conduct an empirical research project. Please note: faculty members from outside the Smith Psychology department are not eligible to serve as thesis advisers; the principal adviser of a psychology honors thesis must be a Smith Psychology Department faculty member. The project culminates in a paper that is equivalent to a publishable journal article in quality and length (i.e., about 30-50 pages of text and written in APA style). At the end of the academic year, Honors students present their projects to the department as a whole. Successful completion of an Honors thesis leads to departmental honors upon graduation.

What are the eligibility requirements?

In order to be eligible for departmental honors, you must have a 3.3 GPA within your major and a 3.0 GPA average for courses outside your major. GPA calculations include all courses taken here at Smith, the Five Colleges and Smith JYA programs. Other transfer credits or JYA program courses are not included.

How should I prepare myself to do an honors thesis?

Students seriously contemplating conducting an honors thesis should begin talking to professors in their area of research interest during their junior year, at the latest. Many honors projects have developed from research that students have done with professors, either by volunteering in their laboratories or through special studies. Besides completing the requirements for the major, we recommend that students thinking about honors take an upper level seminar, laboratory or special studies in the area of research interest. We also strongly recommend that students take Advanced Statistics (PSY 290/MTH 290) during their junior or senior year.

How do I find an honors adviser?

There are several ways to find a faculty member to supervise your honors thesis. Most students begin by volunteering in a faculty member's research laboratory during their first or second years at Smith. This acquaints students with research topics and the nuts and bolts of the research process. Others approach professors of classes that they've especially enjoyed. When a student thinks she knows with whom she wants to work, that student should make an appointment to meet with the professor to discuss the possibility of doing an Honors thesis.

What if I can't find an adviser whose research interests match mine?

The psychology department consists of active researchers studying many exciting topics. Of course, it is possible that our faculty will not be studying the particular topic in which you currently are interested. In this case, you have two options. First, you can ask professors if they would be willing to supervise a thesis outside their area of expertise. Better yet, you can work with a professor to design an honors project that the professor feels comfortable supervising and satisfies your interests as well. We have found that the best experiences occur when student interests can be assimilated into the professor's established research program. Thus, the quality of your training will be enhanced by a good fit between your thesis topic and your adviser's area of expertise.

How do I get approval for honors?

First, you have to complete an application for honors. There are full instructions for the completion of this application on the class deans website. When you are done with your application, you submit it to the director of honors for the psychology department. To enter the honors program, you have to receive approval of your project from both the psychology department and the college's Subcommittee on Honors and Independent Programs (SHIP). First, the psychology department reviews and votes on your honors proposal. If you are approved at the departmental level, the honors director forwards your proposal to SHIP for review and approval.

Can I do honors if I go abroad junior year?

The answer is a most definite "yes," although it will take some planning on your part. You should be prepared to contact your potential adviser before you go away; another option is to approach your potential adviser via email while you are abroad. In any case, do not wait until the beginning of your senior year to make contact, as that will be unfeasible given the submission deadlines (see suggested timeline below).

How is an honors thesis different from special studies?

A special studies is a scholarly project conducted during the junior or senior year under the supervision of any member of the department. It can take the format of either a literature review or an empirical study, and can be worth between 1 to 4 credits. In contrast, the honors thesis is only conducted during the senior year and is subject to an outside approval process. It consists of an empirical study, which you must present before the psychology department in the spring. Presentations usually last 30 minutes, with an additional 20 minutes for questions. Honors theses are worth 12 credits, 6 per semester.

What are the benefits of doing a thesis?

The honors thesis provides you the unique opportunity of immersing yourself in a research project to greater depths than anything else you will experience in the psychology department. Many students report feeling great satisfaction from the experience of taking the lead on a research project, which the honors thesis affords. Your research and writing skills will improve immensely during the process. In addition, the experience may help you focus your research interests when considering a graduate career in psychology.

What are the disadvantages?

The greatest disadvantage is the time commitment, most of which falls during your senior year. The 12-credit requirement also obliges you to take fewer courses during your senior year, which may limit your options. Some students report being intimidated by the writing commitment. However, the psychology department recently has reduced the writing expectations of the final paper to that of a manuscript suitable for publication in a major empirical journal.

What resources are available to support my honors thesis research?

Financial assistance for honors research is available. You can procure funds from the Tomlinson Memorial Fund, administered by SHIP. To request assistance, you need to complete a Tomlinson application, which you receive from the class deans office with the honors application. The Tomlinson request requires a proposed budget and justification of expenses as well as a letter of support from your thesis adviser. You need to submit Tomlinson fund requests at the same time as your honors proposal.

You are required to complete a library instruction session for your honors project during the fall semester. This one-hour session provides instruction in use of the science library's resources to help with your research project.

How are honors evaluated?

First, you are graded by your thesis adviser for the honors credits (typically 12) included on your transcript.

In addition, an official honors designation is given to each thesis at the end of the project based on the student's grades within the major, oral defense of the project, and final written thesis. Two members of the psychology department (an "examiner" and the student's thesis adviser) evaluate the honors student's oral defense. Likewise, two faculty members (a "reader" and the student's thesis adviser) evaluate the honors student's written thesis. The director of honors chooses readers and examiners in consultation with each thesis student and her adviser.

Suggested Timeline for Completing an Honors Thesis

Prior to Spring Semester: Junior Year

- Volunteer in a faculty member's research lab

- Consider taking SDS 290 or PSY 301 (Advanced Statistics) in your junior year

- Take an upper level seminar, laboratory course, or special studies in your area of research interest

Spring Semester: Junior Year

- Find a faculty adviser and create a research plan

- Consider seeking honors approval this semester, rather than waiting until next fall

- Plan courses for senior year; consider taking SDS 290/PSY 301 (Advanced Statistics), if you have not already

Fall Semester: Senior Year

- Submit honors application to the Psychology by the date designated by the director of honors

- Procure Independent Review Board (IRB) approval

- Complete library instruction session

Spring Semester: Senior Year

- Submit expense receipts for the Tomlinson fund, typically by mid-April

- Submit thesis to the department on the deadline determined by SHIP

- Present thesis to psychology department during the last week of classes

- Submit final departmental copy of thesis to the honors director and final library copy to SHIP by the first week in May

The psychology curriculum is structured to develop the skills and objectives set forth in the department's learning goals. Courses are generally organized around the following tracks of study:

- Mind and Brain

- Health and Illness

- Person and Society

These tracks of study have been designed into the requirements for the department's major and minor and are clearly reflected in the courses offered by the department.

Mind and Brain

- PSY 120 Introduction to Cognitive Science

- NSC 125 Sensation and Perception

- NSC 210 Fundamentals of Neuroscience

- EDC 238 Introduction to Learning Sciences

- PSY 209/PHI 209 Philosophy and History of Psychology

- PSY 213/PHI 213 Language Acquisition

- PSY 215 Brain States

- PSY 216 Understanding Minds

- PSY 218 Cognitive Psychology

- PSY 225 Memory in Literature

- PSY 227 Brain, Behavior, and Emotion

- PSY 312 Calderwood Seminar: Psychology in the Public Square

- PSY 313 Psycholinguistics

- PSY 314 Cognition in Film

- PSY 315 Autism Spectrum Disorders

- PSY 317 Seminar in Cross-Cultural Psychology

- PSY 319 Research Seminar in Adult Cognition

- PSY 320 Research Seminar in Biological Rhythms

- PSY 326 Seminar in Biopsychology

- PSY 327 Seminar in Mind and Brain

Health and Illness

- PSY 130 Clinical Neuroscience

- PSY 140 Health Psychology

- PSY 150 Abnormal Psychology

- ESS 220 Psychology of Sport

- EDC 239 Counseling Theory & Education

- PSY 230 Psychopharmacology

- PSY 240 Health Promotion

- PSY 250 Culture, Ethnicity, Mental Health

- PSY 253 Developmental Psychopathology

- PSY 287 Evidence-Based Practice

- PSY 340 Psychosocial Determinants of Health

- PSY 350 Seminar in Culture, Ethnicity, and Mental Health

- PSY 352 Seminar in Advanced Clinical Psychology

- PSY 353 Seminar in Developmental Psychopathology

- PSY 354 Seminar in Advanced Abnormal Psychology

- PSY 355 Practicum Seminar in Clinical Psychology

- PSY 358 Research Seminar in Clinical Psychology

Person and Society

- PSY 165 Adult Development

- PSY 166 Psychology of Gender

- PSY 170 Introduction to Social Psychology

- PSY 180 Personality Psychology

- EDC 235 Child and Adolescent Growth and Development

- PSY 263 Psychology of the Black Experience

- PSY 264 Lifespan Development

- PSY 265 Political Psychology

- PSY 266 Psychology of Women and Gender

- PSY 267 Moral Psychology

- PSY 268 Human Side of Climate Change

- PSY 269 Intergroup Relations

- PSY/REL 304 Happiness: Personal Wellbeing

- PSY 360 Peer Relationships

- PSY/SDS 364 Research Seminar on Intergroup Relations

- PSY 368 Seminar in Identity Development

- PSY 371 Seminar in Personality

- PSY 373 Research Seminar in Personality

- PSY 374 Seminar on Political Activism

- PSY 375 Research Seminar on Political Psychology

- PSY 376 Seminar in Psychology and Law

Additional Courses

- PSY 301 Advanced Research Design and Analysis

- PSY 345 Feminist Perspectives on Psychological Science

Following college precedent, the current curriculum of the Department of Psychology is organized into 100-level introductory courses, 200-level content courses, 300-level labs and seminars and 400-level special studies and honors projects.

In some cases, students also design unique courses of study by incorporating additional classes from other Smith departments, Five College classes not offered at Smith, junior year abroad experiences and original research in the field.

See the Smith College Course Catalog for complete course listings. Students can also take courses through the Five Colleges.

Faculty

Research & Opportunities

Research Opportunities

A continuing goal of the department is to offer significant original research opportunities for declared majors and minors, working closely one-on-one or in small collaborative groups with members of the faculty.

Why Do Research?

Research is a great way of developing and learning new skills. It is an opportunity to acquire experiences that would not be possible to gain any other way. Participating in research allows you to learn about topics in a more complex and practical manner, which cannot be obtained simply from reading a book. These forms of experiences can come from working independently or from being part of a collaboration.

Being involved in research also allows you to develop professional relationships, and is a great way of obtaining mentoring. Your role is simply to acquire the most you can from your research opportunities. Working with faculty on their research not only benefits them, but also serves you well in developing your own research interests. It allows you to see what you are most interested in and how you can further develop these interests. Understanding how to successfully conduct research here at Smith is a valuable and rewarding experience.

Obtaining Psychology Research Experience at Smith

Take a Laboratory Psychology Course

Research experience can be obtained by taking a laboratory course in any areas of psychology. By taking a lab course, you'll learn about the steps needed to conduct a research study. This is a great way to obtain research experience while also earning course credit.

Volunteer in a Faculty Member's Lab

Sometimes faculty do not have paid positions available but do welcome students who are willing to volunteer in their labs. Volunteering in a lab can help you become familiarized with different aspects of research (e.g., running experimental sessions, conference presentations, etc.).

Most faculty members only require that you are motivated to learn from them, and assist them with different aspects of conducting the research they need to conduct.

Undertake an Independent Study

Students can earn upper-division credits for participating in a special studies or honors thesis project with a member of the faculty. To do so, it is advisable to approach a faculty member early in your college career, take courses that will be valuable for completing your own project (for example, Advanced Stats) and work with that faculty member in some ongoing research capacity.

Become a Paid Research Assistant

All active faculty in the department have ongoing research programs. Each year, faculty presents new findings at national and international meetings of learned societies and publishes copiously in scholarly journals. We are eager to involve our majors and premajors in our research. It is a valuable opportunity to learn at first hand the technical skills of doing research in psychology, the methods of processing findings, and the style of preparing manuscripts and posters for publication and presentation. These positions are generally paid prevailing rates for student assistants.

Become a Paid Summer Research Fellow

Every summer, the Clark Science Center awards summer research fellowships, which provide students the opportunity to work with faculty on their research while also receiving a stipend. Faculty members usually take on fellows if they have had them in a class or have worked with them in some sort of prior research context. Students should seek this opportunity by talking with faculty about their interest in such a program. A call for application submissions is announced every spring, so students should be looking out for this opportunity early in the spring semester. This allows sufficient time to talk to a faculty member and then submit a cogent proposal.

Learn more about how to get started in research at Smith College.

In addition to research opportunities, there are a number of other opportunities available to Smith students during the course of the academic year. Here are just a few:

Teaching Assistantships

The success of our introductory course (PSY 100) depends on the contribution of paid student assistants or proctors. Teaching assistants may participate in and lead small group discussion, advise students on the selection and development of paper topics, do interview testing and work with students on their oral presentations. By participating in a general review of psychology, senior majors develop a coherent overview of the diverse areas that constitute psychology today. For those who are planning to apply to graduate school, teaching assistantships provides an excellent review for the Graduate Record Examinations.

Membership in Psi Chi

The psychology department at Smith has established, nurtured and grown a large and active chapter of Psi Chi, The National Honor Society in Psychology. Founded in 1929 for the purpose of "encouraging, stimulating, and maintaining excellence in scholarship of the individual members in all fields, particularly psychology, and advancing the science of psychology," Psi Chi is a national organization comprised of local chapters on more than 600 college and university campuses.

Psi Chi provides academic recognition to its initiates by fact of membership. On a larger scale, local chapters of Psi Chi offer a nurturing climate towards creative development. These local chapters provide programs designed to stimulate and nourish professional growth. Annual national and regional conventions are held in conjunction with other psychological associations. Psi Chi also offers research award competitions, certificate recognition programs and a quarterly newsletter. Psychology majors wishing to apply for membership in Psi Chi at Smith College should visit the organization's website. All applications must be received by mid-February.

Student Liaisons

Psychology majors are selected as representatives who attend psychology department meetings, cast a vote on departmental decisions, and are asked to represent student interests on a wide variety of matters, such as the structure and contents of the curriculum and new faculty hiring. We see our students as participants in the governance of the department. Applications to be selected as a student liaison are sent to psychology majors in September.

[Conference content forthcoming soon]

Facilities

The Department of Psychology at Smith is housed in Bass Hall, with state-of-the-art laboratories and work areas. These include:

Laboratories

Statistics, Experimental Psychology, Health Psychology, and Psychophysiology

In the basement of Bass Hall, there are general laboratories for statistics and experimental psychology. The statistics laboratory is equipped with computers (with dual Windows and Mac OS capabilities) that are also used in courses such as Research Methods. On this floor too are laboratories for health psychology and psychophysiology.

Language Acquisition, Developmental Psychology, and Psychology of Women

On the second floor of Bass Hall are the laboratories for language acquisition, developmental psychology, and psychology of women. In addition, a well-equipped video analysis facility exists for viewing, transcribing, and editing video recordings of behavior.

Cognitive Psychology, Social Psychology, Personality Psychology, and Clinical Psychology

The third floor of Bass Hall contains extensive laboratories for research in cognitive psychology, social psychology, personality psychology, and clinical psychology.

Young Library

On the first floor of Bass Hall, the Young Library is richly equipped for students of psychology, including an excellent collection of both books and journals. Computerized literature searching is also available.

Seminar Room/Lounge

On the fourth floor there is a comfortable seminar room/lounge named in memory of alumna Gale Curtis.

Science Center Animal Quarters

The Science Center maintains Animal Quarters with several species of small laboratory animals, and laboratory space for behavioral experiments adjoins that space.

Smith College Campus School

Students of child development and language acquisition will have the opportunity to observe and conduct approved studies with children in the preschool (Fort Hill) and the Smith College Campus School.

Smith & Five College Resources

Summer and PostBac Research Opportunities List

A list curated by Smith College Psychology Faculty of opportunities for students to gain research experience outside of Smith.

PSYCINFO Online Research Service

This is a direct link to the library's PsychInfo site. You need to be logged on to a Smith College system computer to access this invaluable online resource.

Smith Library Online Psychology Resources

An important link to a number of online resources, websites and journals available through Smith's central library system.

An important link to many online research resources, articles and tools available throughout the Five College system.

Other Resources

American Psychological Association (APA) Style

An excellent resource for additional information about APA style questions.

Association for Psychological Science

This international organization is dedicated to advancing scientific psychology across disciplinary and geographic borders.

This site has a wide range of information for any students who are interested in learning more about what a degree in psychology can do for your future. There are job postings, license requirement information for all 50 states, interesting interviews and more.

A rich resource that aims to make psychology more transparent and open by providing lists of opportunities such as paid internships, virtual graduate school information sessions, post-baccalaureate jobs, and resources for applying to graduate school.

How Research Can Make a Difference

The Society for Research in Child Development has created a series of videos called “Hidden Figures” in Developmental Science to increase the visibility of leading developmental scientists of color who have made critical research contributions. To learn more, start by watching this video on “Increasing Awareness of Developmental Science.”

Hands-On Research Opportunities

Smith psychology majors often have an opportunity to present their research projects, such as these students showcasing a poster at the Society for Research in Child Development convention with professors Jill and Peter de Villiers.

Research at Smith

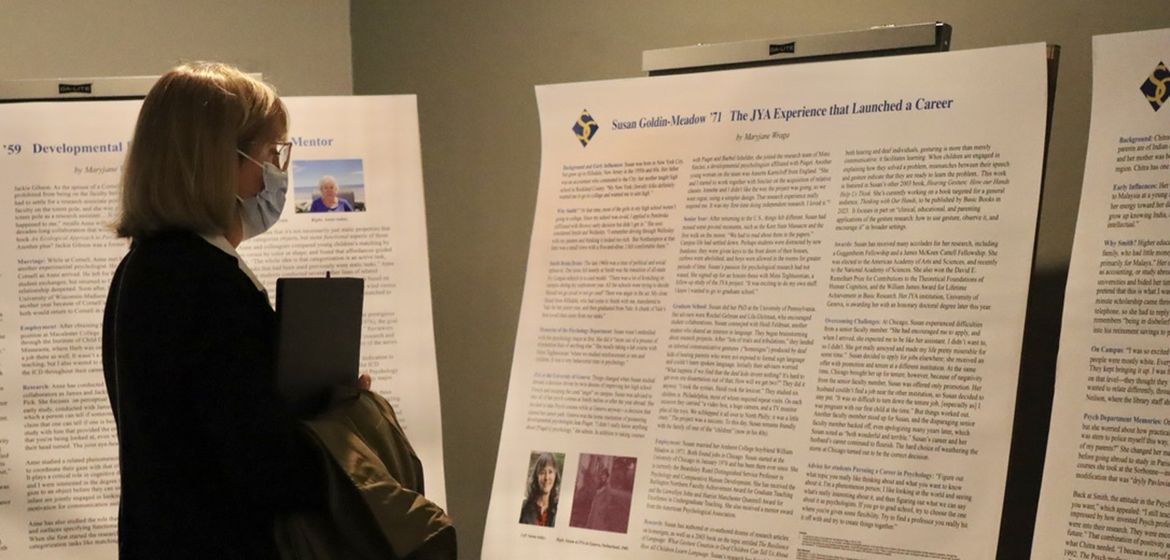

100 Years of Smith Psychologists

The profiles are listed chronologically and reflect developments within the field as well as the department. See what these alums have to say about their time in the department, their research, overcoming obstacles, and advice for undergrads. (Yearbook photos courtesy of Smith College Special Collections.)

Elsa Siipola ’29

Student, Teacher, Researcher, Leader

Background and Early Influences: Elsa Siipola was born in Fitchburg MA in 1908, the daughter of a clerk and department-store window trimmer and a homemaker mother. She was an outstanding high school student, and her teachers encouraged her to apply to Smith. She was able to enroll thanks to scholarships from Smith and the Fitchburg Smith Club, as well as her earnings and savings.

Graduate School: Elsa was promoted to Assistant Professor in 1934. She decided to pursue a PhD in Psychology, choosing Yale because of its interdisciplinary Institute of Human Relations. “I had planned, especially, to attend Clark Hull’s seminar relating behaviorism and psychoanalysis, as well as a course on psychoanalysis taught by my friend Earl Zinn,” she recalled. However, these plans did not pan out. “Hull, the dominant force at Yale at that time, called me to tell me that women were not eligible to take either course. I was shocked and felt cheated.” Hull held other biases as well. While Elsa was graduate student and instructor at Smith, she had attended Kurt Koffka’s weekly seminar on Gestalt Psychology. Koffka had even entrusted her with taking over the undergraduate version of the course when he was ill. At Yale, Hull would refer to Elsa as “the damned Gestalt psychologist,” though this was probably more a case of guilt by association than any actual identification as a Gestaltist.

Back to Smith: Elsa completed her PhD in 1939. In the same year, “after a decade of happy courtship,” she and colleague Harold Israel married. She felt a renewed need for training: “After our marriage I [thought] I should establish my own identity and find an area of psychology different from Harold’s.” Thus, she began postdoctoral work in personality psychology at Harvard, where she studied with Gordon Allport. She also studied psychodynamic and psychoanalytic theory with Henry Murray, then director of the Harvard Psychological Clinic. Following a stint at the Rorschach Research Institute in 1941, she began experimental work on projective tests (her first subject for the Rorschach was Smith Psych major Betty Goldstein ‘43 [later Friedan]. “She took eight hours.”) Elsa used a sabbatical in 1948-49 to study at Worcester State Hospital’s Research Division and later at UCLA. Thereafter she settled into a long career at Smith’s Department of Psychology. She was appointed Associate Professor in 1945 and Professor in 1954 and served as chair of the department several times. She retired in 1973.

Research interests: Elsa is best known for her research on projective techniques, especially the Rorschach. She brought experimental rigor to the challenge of determining general principles by designing a “deliberate program for varying drastically the inviolate conditions of some prominent projective techniques.”2. For example, how does time pressure—or lack of it—affect participants’ responses? Her studies revealed that different “associative products” occur when participants have unlimited time to take the test: “The associative process undergoes a fundamental change in character rather than merely being slowed in pace.”3 In these studies and others, she sought principles that could apply generally to projective techniques—whether word associations or ink blots—and shed light on what is going on when participants interpret test items.

Teaching: Elsa’s intensive study of personality via projective testing led to a teaching focus on personality and depth psychology. For example, in 1949, she co-taught general psychology, served as director of the honors program, taught introduction to experimental psychology, a course on personality, and a seminar in the psychology of personality that included supervised practice with projective techniques. Quite an impressive workload! In the 1950s and 1960s, she continued to combine teaching of the introductory course with courses and seminars in personality. In an era when visual aids in the classroom usually consisted of chalk marks on a blackboard, Siipola’s vivid diagrams of ego, id, and superego stood out. They covered pages of my [Leah Holden’s] notebooks and made personality structures memorable. Upon her retirement, she reflected on teaching at Smith, where “the quality of undergraduate teaching has first priority.”4 It is clear how important teaching was to her, both as a professor and a student. “I…had gifted teachers at Smith, and at Yale when studying for my PhD, and later at Harvard….Whatever modest success I have had in my career, I owe to my teachers.”

Leadership: Elsa’s multiple terms as chair of the department gave her ample opportunity to leave a mark on it. She found a way to lead collaboratively. For a time, she and colleagues William Taylor and Harold Israel devised a system for governing by triumvirate—no matter which of the three was named chair—by having themselves appointed to the long-range planning committee. “The procedure had many virtues. It provided long-range planning. It resolved privately strong disagreements among full professors. It prevented the building up of factions within the department. It was efficient. The plans submitted usually obtained a majority vote, since three positive votes were secured in advance.” She extended her skills to the community through positions on the Governor’s Advisory Committee on Service to Youth, the National Science Foundation’s Committee on Undergraduate Science Instruction, and the Board of Directors of the Smith College Alumnae Association. She also served the college through her membership on the Post-War Planning Committee and by helping to create the Smith College Medal.

Footnotes

1 Except as noted, all quotes come from a 1981 interview of Elsa Siipola by Fran Volkmann, recording and transcription in Smith College Archives.

2 Siipola, Walker & Kolb 1955, p. 441

3 Sippola et al. 1955, p. 445

4 Elsa Siipola, “Looking back,” undated handwritten manuscript, Smith College Archives.

5 Interview of Peter Pufall and Don Reutner by Leah Holden, June 2018.

6 Diedrick Snoek, “Elsa Margareeta Siipola, Professor Emeritus of Psychology,” in the Smith Alumnae Quarterly, 1973.

7 The current Harold Edward Israel and Elsa Siipola Israel Professor of Psychology is Nnamdi Pole.

Select Publications

Fiester, S., & Siipola, E. (1972). Effects of time pressure on the management of aggression in TAT stories. Journal of Personality Assessment, 36(3), 230-240.

Siipola, E. (1940). Implicit or partial reversion errors: a technique of measurement and its relation to other measure of transfer. Journal of Experimental Psychology 26, 53-73.

Siipola, E., & Israel, H.E. (1933). Habit-interference as dependent upon stage of training. American Journal of Psychology 45, 205-227.

Siipola, E., & Taylor, V. (1952). Reactions to ink blots under free and pressure conditions. Journal of Personality, 21, 22-47.

Siipola, E., Walker, N., & Kolb, D. (1955). Task attitudes in word association, projective and nonprojective. Journal of Personality, 23, 441-459.

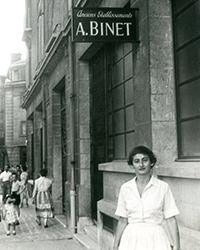

Molly Harrower Ph.D. ’34

From Socialite to Secretary to Psychologist

Background: Mary “Molly” Harrower was born in 1906 to Scottish parents. She grew up in a small village outside of London. As a girl she was an avid writer of fiction and would eventually publish a play and a book of poems called Plain Jane. Despite these proclivities and the fact that several family members had been prominent academics, her parents never considered Molly suitable material for university. The sole reason? Her gender. At age seventeen, Molly was instead sent to finishing school in Paris, to be prepared for becoming “the good wife of a wealthy gentleman.”1 She found the entire experience “miserable,” and credited her parents’ wisdom for taking her out of the school after the first semester and sending her to Switzerland to study French instead. Molly soon realized that she wanted to pursue higher education. Unfortunately, her debutante credentials fell far short of the highly competitive and rigorous British requirements for applying to college. Through a family friend at the University of London, she learned of a program at its constituent Bedford College—a three-year academic diploma in Journalism that didn’t require entrance exams. Molly got in and began fulfilling the journalism requirements, taking several courses in Psychology along the way. One of her Psychology professors, Beatrice Edgell,2 recommended that she switch her focus to Psychology. Molly happily complied. Before her final year, financial misfortune befell her family, and Molly had to withdraw from the program. She left in 1926 with just two of the three years of coursework completed.

Other Smith Memories: Molly was popular on campus. “With my British heritage and an intimate knowledge of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, I was asked to direct a student performance of the Mikado and acted in the faculty’s production of Trial by Jury.” She also has fond memories of hiking in Hampshire County. “Excursions into the surrounding country were almost unbelievable to someone brought up within the confines of Greater London.”5

Early Neuropsychologist: In 1937, after a three-year stint as Director of Students at Douglas College, Molly used a scholarship she had received from the Rockefeller Medical Foundation to work on research that connected two disparate fields at that time: psychology and medicine. She first worked with neurologist Kurt Goldstein at Montefiore Hospital in New York City (where she wasn’t allowed to eat in the doctor’s dining room because of her gender), and then neurologist Wilder Penfield at the Montreal Neurological Institute. From 1938-1942, her job as the staff psychologist at the institute was to monitor patients (operated on by Penfield) for post-surgical cognitive and emotional changes. It wasn’t an easy task. She was “the only woman in the hospital, the only woman fellow, the only woman on the staff, and the only psychologist. It was a very lonely and extraordinary time.”6 In addition to publishing her findings, Harrower developed and copyrighted a group version of the Rorschach test that could be administered to hundreds of patients at a time. In 1938, Molly married Penfield’s assistant, neurosurgeon Theodore Erickson. In 1942, they moved to his new position at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; however, nepotism rules at the university precluded her (as Erickson’s wife) from working there. This caused tension in the marriage, and they divorced in 1944.

Contributions to the War Effort: During World War II, Molly became a consultant to several U.S. military organizations interested in her group Rorschach test. As a consultant for the Surgeon General’s Office, she developed another diagnostic tool called the stress tolerance test—an offshoot of her Rorshach—that was administered to soldiers to assess whether they were mentally fit to go back to battle after exposure to trauma. She would consult for several other organizations throughout her career.

Professional Activities: Molly was president of the New York Society of Clinical Psychologists (1952-53), as well as the Society for Projection Techniques (1941-42). She received an honorary degree from the University of Florida in 1981.

Mentors: Molly attributed her success to the support of two people: her mother and Kurt Koffka. She and Koffka were correspondents from 1927—shortly before she began working for him—until his death in 1941. Her 1984 biography, Kurt Koffka, An Unwitting Self-Portrait, was nominated for the History of Science Society’s Pfizer Prize.

Secret to a Happy Career: “My style of functioning…is guided entirely by what I would call ‘listening to what I want to do.’”8 Throughout her career, she was “free to be myself, and have managed never to take a job I didn’t want, never to do anything or tie my time up in a way I didn’t want it tied up…nothing has diverted or frustrated me…Looking back, I have a feeling of great satisfaction at the unification of the whole thing.”9 Molly died in 1999.

Footnotes

1 Harrower, M. (26 November 1982). "University of Florida Oral History Project" (Interview). Interviewed by Emily Ring. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

2 Edgell was the first woman in Britain to receive a PhD in Psychology, in 1901.

3 Harrower, M. (1984). Memories and milestones: Molly Harrower. In D.P. Rogers (Ed.), Foundations of Psychology: Some Personal Views (pp. 98-137). New York: Praeger.

4 Harrower, M. (1984), p. 105.

5 Harrower, M.R. (1983). Molly R. Harrower. In A.N. O’Connell and N. F. Russo (Eds.). Models of Achievement: Reflections of Eminent Women in Psychology (pp. 220-232). NY: Columbia University Press.

6 Harrower, M. (26 November 1982). "University of Florida Oral History Project" (Interview). Interviewed by Emily Ring. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

7 Dewsbury, D.A. (2000). Molly R. Harrower (1906-1999). American Psychologist, 55(9), 1058.

8 Harrower, M.R. (1983). Molly R. Harrower. In A.N. O’Connell and N. F. Russo (Eds.). Models of Achievement: Reflections of Eminent Women in Psychology (pp. 220-232). NY: Columbia University Press.

9 Harrower, M. (26 November 1982), p. 18.

Select References

Harrower, M. (1961). The Practice of Clinical Psychology. New York: Charles C. Thomas.

Harrower, M. (1972). The Therapy of Poetry. New York: Charles C. Thomas.

Harrower, M. (1976). Rorschach records of the Nazi war records: An experimental study after thirty years. Journal of Personality Assessment, 40(4), 341-351.

Harrower, M. (1986). The Stress tolerance test. Journal of Personality Assessment, 50(3), 417-427.

Koffka, K., & Harrower, M.R. (1931). Colour and organization, part I. Psychologische Forshung, 15, 145-192.

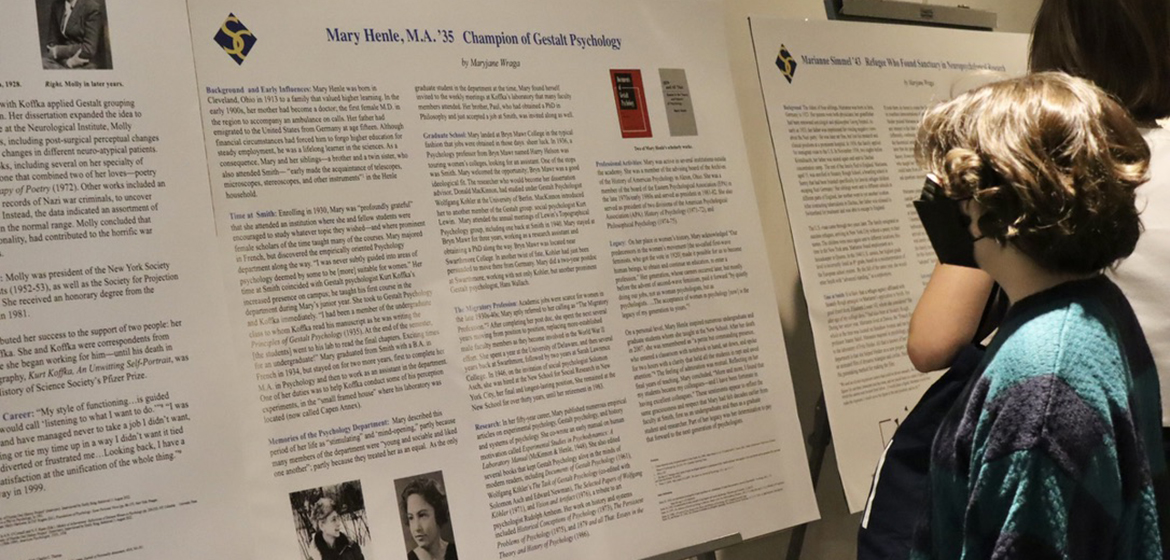

Champion of Gestalt Psychology

Background and Early Influences: Mary Henle was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1913 to a family that valued higher learning. In the early 1900s, her mother had become a doctor; the first female doctor in the region to accompany an ambulance on calls. Her father had emigrated to the United States from Germany at age fifteen. Although financial circumstances had forced him to give up plans of higher education for steady employment, he was a lifelong learner in the sciences. As a consequence, Mary and her siblings—a brother and a twin sister— “early made the acquaintance of telescopes, microscopes, stereoscopes, and other instruments”1 in the Henle household.

Mary graduated from Smith with a B.A. in French in 1934, but stayed on for two more years, first to complete her M.A. in Psychology and then to work as an assistant in the department. One of her duties was to help Koffka conduct some of his perception experiments, in the “small framed house” off campus where his laboratory was located (now called Capen Annex).

Memories of the Psychology Department: Mary described this period of her life as “stimulating” and ‘mind-opening,” partly because many members of the department were “young and sociable and liked one another”; partly because they treated her as an equal. As the only graduate student in the department at the time, Mary found herself invited to the weekly meetings at Koffka’s laboratory that many faculty members attended. Her brother, Paul, who had obtained a PhD in Philosophy and just accepted a job at Smith, was invited along as well.

Graduate School: Mary landed at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania in the typical way that research jobs were obtained in those days: sheer luck. In 1936, a Psychology professor from Bryn Mawr named Harry Helson was touring women’s colleges, looking for an assistant. One of the stops was Smith. Mary welcomed the opportunity; Bryn Mawr was a good ideological fit. A researcher there who would become her dissertation advisor, Donald MacKinnon, had studied under Gestalt Psychologist Wolfgang Kohler at the University of Berlin. MacKinnon introduced her to another member of the Gestalt circle: social psychologist Kurt Lewin. Mary attended the annual meetings of Lewin’s Topographical Psychology group, including one back at Smith in 1940. Mary stayed at Bryn Mawr for three years, working as a research assistant and obtaining a PhD along the way. In another twist of fate, Kohler had just been persuaded to move from German to nearby Swarthmore College. Mary did a two-year postdoc at Swarthmore, working with not only Kohler, but another prominent Gestalt psychologist, Hans Wallach.

The Migratory Profession: Academic jobs were scarce for women in the late 1930s-40s; Mary aptly referred to her calling as “the Migratory Profession.”2 After completing her post doc, she spent the next several years moving from position to position, replacing more-established male faculty as they become involved in the World War II effort. She spent a year at the University of Delaware, and then several years back at Swarthmore, followed by two years at Sarah Lawrence College. In 1946, on the invitation of social psychologist Solomon Asch, she was hired at what was then called the New School for Social Research, in New York City, her final and longest-lasting position. She remained at the New School for over thirty years, until her retirement in 1983.

Research: In her fifty-year career, Mary published numerous empirical articles on experimental psychology, Gestalt psychology, and history and systems of psychology. She co-wrote an early manual on human motivation called Experimental Studies in Psychodynamics: A Laboratory Manual (McKinnon & Henle, 1948). She also edited several books that kept Gestalt Psychology alive in the minds of modern readers, including Documents of Gestalt Psychology (1961), Wolfgang Köhler’s The Task of Gestalt Psychology (co-edited with Solomon Asch and Edward Newman), The Selected Papers of Wolfgang Köhler (1971), and Vision and Artifact (1976), a tribute to Rudolph Arnheim. Her work on history and systems included Historical Conceptions of Psychology (1973), The Persistent Problems of Psychology (1975), and 1879 and all That: Essays in the Theory and History of Psychology (1986).

Professional Activities: Mary Henle was active in several institutions outside the academy. She was a member of the advising board of the Archives of the History of American Psychology in Akron, Ohio. Henle was a member of the board of the Eastern Psychological Association (EPA) in the late 1970s/early 1980s and served as president in 1981-82. She also served as president of two divisions of the American Psychological Association (APA): History of Psychology (1971-72), and Philosophical Psychology (1974-75).

On the personal level, Mary Henle inspired numerous undergraduate and graduate students whom she taught at the New School. After her death in 2007, she was remembered as “a petite but commanding presence, who entered a classroom with notebook in hand, sat down, and spoke for two hours with a clarity that held all the students in rapt and awed attention.”4 The feeling of admiration was mutual. Reflecting on her final years of teaching, Mary concluded, “More and more, I found that my students became my colleagues—and I have been fortunate in having excellent colleagues.” These sentiments appear to reflect the same graciousness and respect that Mary had felt decades earlier from faculty at Smith, first as an undergraduate and then as a graduate student and researcher. Part of her legacy is that she paid that forward to the next generation of psychologists.

Footnotes

1 Unless otherwise noted, all quoted material is from Henle, M. (1983). Mary Henle. In A.N. O’Connell and N. F. Russo, Eds. Models of Achievement: Reflections of Eminent Women in Psychology (pp. 220-232). NY: Columbia University Press.

2 Henle (1983), p. 225.

3 The idea of a “between-wave” group of quiet but diligent feminists is reminiscent of the “stealth feminism” label applied to Tomi-Ann Roberts and her generation fifty years later (see Tomi-Ann Roberts ’85 profile).

4 Porac, C. (2009). Mary Henle (1913-2007). The American Journal of Psychology, 122, 1, pp. 111-113.

Select Publications

Henle, M. (1942). An experimental investigation of past experience as a determinant of visual form perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 30(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0056500

Henle, M. (1944). An examination of some concepts of topological and vector psychology. Character and Personality, 12, 244-255.

Henle, M. (1977). The influence of Gestalt psychology in America. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 299,1, 3-12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1977.tb53054.x

Henle, M. (1986). 1879 and all that: Essays in the theory and history of psychology. NY: Columbia University Press.

Henle, M., and Michael, M. (1956). The influence of attitudes on syllogistic reasoning. The Journal of Social Psychology, 44, 115-127. DOI: 10.1080/00224545.1956.9921907

Refugee Who Found Sanctuary in

Neuropsychological Research

Background: The oldest of four siblings, Marianne was born in Jena, Germany in 1923. Both of her parents were physicians; her grandfather was renowned sociologist and philosopher Georg Simmel. As early as 1933, her father was imprisoned for voicing negative views about the Nazi party.1 He was later set free, but lost his research and clinical positions at a prominent hospital. In 1936, the family applied for immigrant visas to the U.S. In November 1938, two nights before Kristallnacht, her father was seized again and sent to Dachau concentration camp. The rest of the family fled to England. Marianne, aged 15, was enrolled in Stoately Rough School, a boarding school in Surrey that had been founded specifically for Jewish refugee children escaping Nazi Germany.2 Her siblings relocated to different schools in different parts of England; their mother was in yet another location. After contracting tuberculosis at Dachau, her father was released to Switzerland for treatment and was able to escape to England. The U.S. visas finally came through two years later. The family emigrated as stateless refugees, arriving in New York City without a penny. The children were once again sent to different places, this time in the New York area. Marianne found employment as a housekeeper in Queens. In the 1940 U.S. census, her highest grade level is incorrectly listed as 8th grade, based on a misinterpretation of the European school system. By the fall of the same year, she would enter Smith with “advanced standing,” as a sophomore.

“We used an old moving-picture camera that could be driven manually. We had cardboard figures for our three characters and the room, and we placed them on a sheet of glass, on which the camera was focused from below…I would place a figure; Marianne would then make the exposure; I would move the figure to the next position; and so on.”4

It took them six hours to create the three-minute film, which has been used in countless demonstrations of apparent behavior ever since. Although Heider praised Marianne as one of the few students at Smith “who had any interest in the ideas that I was concerned with,”5 she recalled differently, confessing decades later that she hadn’t really understood the theoretical underpinnings of her undergraduate project. It was only later that she gained a deeper appreciation for Heider’s attribution theory. However, she always regarded him as an important mentor, who taught her “probably the most important thing any undergraduate could learn from a professor...how to follow a problem, to analyze it, to ask questions insistently, not to settle for the once-over quick answers.”6

Marianne jokingly claimed that informal interactions with the Heider family outside of the lab also afforded her a bonus education in cultural anthropology. “Grace [Heider] welcomed me into the Heider family, and at times, and with whatever reservations, entrusted the three boys to me. I learned much about life in the United States.”7 Marianne also befriended the family of Smith President Herbert Davis, who had arrived on campus the same year as she. As a native of England, Davis was keenly aware of the refugee crisis that Nazi Germany had created; his family hosted five young European refugees at the president’s house. Marianne referred to the Davis’s as her “adopted” family; they kept in touch through letter writing for decades.8

Internship: In 1943, the spring of her senior year, Marianne applied for a Psychology internship at Worcester State Hospital to study neuropsychology. Because she wasn’t yet a U.S. citizen, her application hit a snag, and Marianne only found out that she had been accepted weeks before the internship started. She worked with Chief Psychologist David Shakow, who would become a mentor and lifelong friend. “I was very young and green when I came to Worcester,” she recalled. “I had never seen a hospitalized psychotic patient. I got lost that first day, and was not able to leave a locked ward after the attendant had taken the keys from me. I always wondered whether that was part of the ‘educational plan.’”9

Graduate School: Marianne left Worcester after two years to begin graduate study at Harvard, where she received her M.A. in 1945 and her Ph.D. in 1948. Her doctoral thesis advisor was Eugenia Hanfmann, a Russian refugee who had arrived in the U.S. ten years earlier than Marianne to work as an assistant in Kurt Koffka’s laboratory at Smith. They would become close friends. Marianne’s doctoral thesis was entitled “A study of qualitative individual differences in thinking and problem solving.” To earn money while studying, she took adjunct lecturer jobs in several colleges nearby, including Cambridge Junior College and Wellesley.

Employment: Her first faculty position was at the College of Medicine at the University of Illinois in Chicago. She also served as assistant director of the Illinois State Psychopathic Institute. Around 1961, she joined the Psychology Department at Brandeis University, where she was reunited with friend and mentor, Eugenia Hanfmann. Marianne was a valued teacher. “She was demanding but also supportive, and the contacts she made with her students lasted long after their graduation, with Marianne always ready to intercede on their behalf.”10

Professional Activities: In 1949, Smith awarded Marianne an Alumna Phi Beta Kappa. She was awarded diplomate status in clinical psychology from the American Board of Examiners in Professional Psychology; she was a fellow of five divisions of the American Psychological Association, including Society for the Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, for which she served as president in 1969–1970. In 2004, she received the Farnsworth Award from the latter society.

Overcoming Challenges: As a refugee who had fled Nazi Germany, Marianne struggled to feel secure in her adopted country. In her first year at Smith, she had applied to become a naturalized U.S. citizen; after the obligatory five-year waiting period, she was naturalized in 1945 while attending Harvard. Yet three years later, in a letter to David Shakow, she was still experiencing apprehension: “I am just developing a new type of paranoia: No matter what government, when and where—the government is always down on me.” 11

The Heider and Simmel Legacy: Early in her career, Marianne wrote to Heider to request a copy of the Heider-Simmel film for her own research. Her use of the possessive pronoun in the ask (“I would like to use our little movie with some of my [current] patients”12) denotes her sense of involvement in the project. The association was sometimes awkward, however. “Throughout my academic career, whenever I met a new colleague…the immediate reaction was always ‘you are the Simmel of Heider and Simmel,’ … often followed, perhaps a bit more hesitantly, by ‘but you didn’t stay in that kind of work.’”13 When supplying biographical information in later years, Marianne sometimes omitted the most famous research project of her career.

Footnotes

1 Thanks to Marianne’s brother, Dr. Arnold Simmel, for meeting to discuss Marianne and their early family life. Interviewed by Maryjane Wraga on August 1, 2022.

2 https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/hmd2019/ .Downloaded on 7/28/22.

3 Thanks to Leah Holden ’68 for retrieving information on Marianne from the History of American Psychology Archive.

4 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

5 Heider, F. (1983). The life of a psychologist. (p. 148). Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas.

6 Heider, F. (1983), p. 152.

7 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

8 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

9 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

10 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

11 Golumb, C. (2012). Marianne L. Simmel (1923-2010). American Psychologist, 67(2),162. [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

12 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

13 [Box No. M6610-M6630, Correspondence Folder, Marianne Simmel papers], Archives of the History of American Psychology, The Cummings Center for the History of Psychology, The University of Akron.

Select References

Heider, F., & Simmel, M. (1944). An experimental study of apparent behavior. The American Journal of Psychology, 57, 243-259. https://doi.org/10.2307/1416950

Meyer, E., & Simmel, M. (1947). The psychological appraisal of children with neurological defects. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42(2), 193-205.

Simmel, M.L. (1953). The coin problem: A study in thinking. The American Journal of Psychology, 66, 229-241.

Simmel, M. (1956). On phantom limbs. A.M.A. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry,75, 637-647.

Simmel, M. (1972). Notes on the creation of the perceptual object. Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism, 31(2), 193-200.

Anne Danielson Pick ’59

Developmental Psychologist and Dedicated Mentor

by Maryjane Wraga

Background: Anne grew up in the 1940s and 50s in Sycamore, Illinois. “It was a small town,” she recalls, “and it was in the era when girls were not encouraged to speak up much in school. Girls were not supposed to be brainy. If they were, they were not supposed to show it.”1

Psych Department Memories: Anne first considered majoring in sociology, but after taking an introductory course, she felt that the focus was too distant. “It gave me this image of somebody sitting on a platform up high watching all the little creatures on earth run around.” Psychology was a better fit for Anne’s wish to work with people; however, figuring out precisely how required further exploration. “One of the [Psych] courses I took was on the Rorschach [Test], with Professor Elsa Siipola. It convinced me that I did not want to do clinical psychology.”

In the 1950s, the Psychology department was housed in Pierce Hall.2 “There weren’t any labs,” Anne recalls. She settled on an honors thesis with faculty member Richard Teevan—a survey measuring “need for achievement,” where participants had to “interpret different scenarios or pictures.” The subject pool? Her classmates. Her “personal and intellectual” interactions with Teevan and also developmentalist Elinor Wardwell [later Ames] had the greatest impact on Anne during her time at Smith. They nurtured her interest in research and in the study of human development.

Graduate School: Like many seniors, Anne had “not a clue” as to what she wanted to do after graduation. She took the National Security Agency exam and scored well. However, she had a moment of enlightenment: “I do not want to spend my time breaking codes.” She applied to the Iowa Child Welfare Research Station and was accepted, but its name put her off. “You can see how carefully this was all thought out,” she recalls with a laugh. She applied to a Psychology PhD program at Johns Hopkins. The reply? “Thank you, but we don’t accept women.” It was Smith faculty member Elinor Wardwell who was the “conduit” to Anne’s future career. Wardwell was a Cornell PhD candidate teaching at Smith while she finished her dissertation. She telephoned her Cornell mentor Eleanor “Jackie” Gibson and told her about Anne’s interest in Psychology; Jackie encouraged Anne to apply.

Anne was accepted by Cornell, but despite having graduated from Smith with Honors, she was passed over for a prestigious teaching assistantship. Instead, she was awarded a research assistantship with Jackie Gibson. As the spouse of a Cornell faculty member,3 Jackie was prohibited from being on the faculty because of their nepotism rule; she had to settle for a research associate position. “Jackie was the low faculty on the totem pole, and she was given the low student on the totem pole as a research assistant...It was the best thing that ever happened to me,” recalls Anne with a smile. She and Jackie began a decades-long collaboration that would culminate in the 2002 classic book An Ecological Approach to Perceptual Learning and Development. Another plus? Jackie Gibson was a former Smithie from the class of 1931.

Marriage: While at Cornell, Anne met her husband, Herb Pick—another experimental psychologist. He was finishing up his PhD at Cornell as Anne arrived. “His parents hosted a big party for the four or five students who graduated that year, and I got invited.” He left for Russia on one of its first graduate student exchanges, but returned to Cornell the following summer. Their relationship deepened. Soon after, Herb left to begin his first job at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Anne was able to join him after another year because of Cornell’s flexible residency requirements. They both would return to Cornell in summers while she finished her degree.

Employment: After obtaining her PhD in 1963, Anne landed a teaching position at Macalester College. She was also part of a research grant through the Institute of Child Development (ICD) at the University Minnesota, where Herb was now on the faculty. Anne was eventually offered a job there as well. It wasn’t a difficult decision to make. “I loved teaching, but I also wanted to do research.” She and Herb remained at the ICD throughout their careers and until his passing in 2012. Along the way, they took advantage of opportunities for sabbatical leaves at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda, and at Katholieke Universiteit in Nijmegen, Netherlands.

Research: Anne has conducted research with such distinguished collaborators as James and Jackie Gibson, as well as her spouse, Herb Pick. Her studies have focused on perceptual learning in both children and adults. One early study, conducted with James Gibson, examined the precision with which a person can tell if someone is looking at them. “[James] would claim that one can tell if one is being looked at; Anne conducted a study with him that provided the empirical evidence. “You can perceive that you're being looked at, even when the person looking at you has their head turned. The joint eye-head position provides the information.”

Anne studied a related phenomenon in infants—joint attention, the ability to coordinate their gaze with that of a caregiver toward the same object. It plays a critical role in cognitive development. “My graduate students and I were interested in the degree to which you can direct an infant's gaze to an object or event before they can use pointing. Once the adult and the infant are jointly engaged in looking at something, it provides enormous motivation for communication and scaffolds all kinds of learning.”

Anne had a five-year run editing the sixth to tenth volumes of the prestigious series Minnesota Symposia on Child Psychology (1972 - 1976), the goal of which was to represent “cutting-edge work in the field.” Reviewers praised her for putting together an “outstanding” collection of contributions and for “maintaining the high standard”4 set in earlier volumes of the series.

Distinguished Award: Anne is also well known for her dedication to mentoring undergraduates at the ICD. To honor this achievement, the ICD established the Anne Pick Award for an Outstanding Child Psychology Major, given annually to one undergraduate child psychology major.

Overcoming Challenges: It was difficult to be a woman with three young children while on the tenure clock. “It required a lot of juggling. Herb and I would cover for each other. I had a 75%-time appointment for many years. And we had a wonderful ‘Grandma Black’ who helped out every day. I would be in the department from 10 to 4. At some point I realized that my [full-time male] colleagues were working at home one or more days a week. Their students were coming to my office while they stayed home.” Anne was able to petition successfully for full-time employment.

Advice for Students Pursuing a Career in Psychology: Anne offers a simple adage that reflects the success of her own research career: “Do what you want to do!”

Footnotes

1 Unless otherwise indicated, all quoted material is from an interview with Maryjane Wraga on August 18, 2022.

2 In 1964, the department moved to more spacious accommodations on two floors of Burton Hall as part of a consolidation of the Science Center. In the early 1990s, Psychology moved to its current home of Bass Hall.

3 Jackie Gibson ’31 was married to James Gibson. Both were professors at Smith before leaving for Cornell in 1949.

4 Lipsitt, L.P. (1977). From a classic series. Contemporary Psychology, 22(8), 586-588.

Select References

Flom, R., Barrick. L.E., & Pick, A.D. (2018). Infants discriminate the affective expressions of their peers: The roles of age and familiarization time. Infancy, 23(5), 692-707.

Gibson, E. J., & Pick, A.D. (2000). An ecological approach to perceptual learning and development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smitsman, A. W., van Loosbroek, E., & Pick, A. D., (1987). The primacy of affordances in categorization by children. British Journal of Develomental Psychology, 5, 265-273.

Soken, N., & Pick. A.D. (1992). Intermodal perception of happy and angry expressive behaviors by 7-month-old infants. Child Development, 63, 787-795.

Ziemer, C.J., Plumert, J.M., & Pick, A.D. (2012). To grasp or not to grasp: Infants’ actions toward objects and pictures. Infancy, 17, 479-497.

Lynn Hasher ’66

Paying Attention to Things of Value

by Maryjane Wraga

Background: Lynn grew up in the Bronx, New York, until the sixth grade (1950s), when her family moved to Levittown, Pennsylvania. She has two younger sisters.

Early Influences: Lynn’s education in the New York City schools put her two years ahead of the Falls Township curriculum. Her teacher there had “no clue what to do with me.”1 The solution was to have Lynn tutor a woman with serious intellectual and physical challenges. The patient had anterograde amnesia—the inability to form new long-term memories—although Lynn obviously wasn’t aware of this diagnosis at the time. “I would sit with Claire and teach her something, and by the end of the session she seemed to understand. But the next day she couldn’t remember what we had done. I was fascinated by how that could possibly be.” This experience would stay with Lynn for years.

Lynn was also an avid reader, devouring “whatever was available in the Levittown Public Library,” and before that, the small local branch of the New York Public Library. Her parents were “adamant that [Lynn and her sisters] would go to college,” and they lived “very frugally” so there would be enough money for all three to go. “I never really considered not going to college.”

Why Smith? Lynn’s journey to Smith started with an announcement on the bulletin board outside her high school guidance counselor’s office, featuring a picture of Capen House. The posting advertised a scholarship to Smith, available for “a person from the Philadelphia area who walked on water.” Lynn was motivated to apply: “My sisters were coming up behind me.” Her guidance counselor also advised that scholarships to all-women colleges would be easier to obtain than those for coed schools. Lynn applied and got the scholarship, “despite not matching all of those qualities,” she is quick to add. When two alums from the local Smith club visited her home for a final interview, Lynn’s mother sealed the deal by putting out “all of her cracked dishes” to ensure that the College understood Lynn’s financial need.

Despite the changing times, the majority of Smith students in the early 1960s seemed relatively conservative. By her senior year, Lynn had become more politically active. While in charge of some house activities, she invited an SDS (Students for Democratic Society) group from Wesleyan to come and talk. “My housemates were horrified by these people.”

Psych Department Memories: Lynn initially gravitated to Religious Studies, but her parents advised her to major in something more practical/employable. Lynn had taken Intro Psych and enjoyed “the experimental side, the analytic aspect of it.” She remembers the home of the Psychology Department—Pierce Hall—as having “a few small rooms” for conducting studies, one of which was used by recent hire Bob Teghtsoonian. She remembers exiting Pierce Hall one evening when several faculty members were outside demonstrating techniques for viewing the moon illusion.2

An Experimental Psychology course on Human Learning that Lynn took with faculty member Barbara Musgrave set her on a new path. At the time, research on nonhuman animals dominated the field; the 500-page textbook for Musgrave’s course had “maybe fifty pages” on human learning and memory.3 What little human research was out there involved iterations of one experimental procedure—memorizing lists of nonsense syllables. “The idea was that you could understand the acquisition of knowledge by studying these little building blocks.” Musgrave and fellow faculty member, Jean Cohen, disagreed. “They wrote a paper on the importance of using real-world materials rather than nonsense syllables. Other [memory and learning] researchers pooh-poohed it.” The importance of ecological validity in empirical research is now widely acknowledged. “[Musgrave and Cohen] were at least fifteen years ahead of their time.” The course reignited Lynn’s interest in human memory. She did an honors thesis with Musgrave titled “The Effect of Overtraining on Abstraction in Verbal-Associate Learning.”

Graduate School: Lynn knew she wanted to pursue memory studies in grad school. She turned to Barbara Musgrave for advice; Musgrave steered her to the best people in the field. “I applied to Stanford, Northwestern, Berkeley, and Harvard without any knowledge of how difficult it would be to get in. The person at Stanford had decided that he was going to be a clinical psychologist because he was tired of nonsense syllables, so he wasn't taking any students. I didn't get into Harvard; I might have been waitlisted. The person at Northwestern had had a terrible experience with a woman graduate student and swore he would never take another.” Luckily, Leo Postman at Stanford viewed women graduate students favorably, and he perceived graduates of a women’s colleges as having a particular advantage. “Postman believed that we could all write well, and that mattered to him greatly. Hence my admission.”

Lynn found the cultural changes occurring between 1966 and 1970—her time as a PhD student at Berkeley—to be even greater than what she had experienced as a Smith undergrad. “The Vietnam war was on, and because I had grown up in a working-class neighborhood, I knew boys who were drafted or who volunteered. I got letters from a few of them in Vietnam. I was really much more shaken by that.”

There were also student protests on Berkeley’s campus. “I lived on the edge of People's Park. I was there when the riot occurred, and a student was killed. There were several times when I could not go home because the Psychology building was on the north side of the campus, and I lived on the south side. The tear gas was on the south side.” On such occasions, Lynn would stay with a fellow Smithie (working on her PhD in history) in Oakland.

The tension on campus continued. “One day I went out of my apartment to go running and I got to the corner, just off of Telegraph Avenue, the main drag for students. There were four military guys with bayonets sticking up from their rifles. So I crawled back home. It was the creepiest thing I had seen to that point in my life.”

Amidst all the chaos, Lynn worked as a part-time research assistant for Postman for twenty hours a week, all the way through her last year of graduate school. In her spare time, Lynn did “various whack- a-doodle experiments,” none of which actually worked. For example, in one study she presented incomplete sets of related items to participants, and memory for that information was tested (e.g., summer, winter, spring; knife, spoon). The research question was whether the missing counterparts [e.g., “fall” or “fork”] would be recalled. “I found no such evidence! I've always been interested in experimental topics that are off the beaten track.” Lynn was not daunted by these disappointments. “My publications as a grad student were on projects I had helped collect data for,” such as a recognition task on which kindergarteners and college students did equally well. She graduated with a Ph.D. in Psychology in 1970.

Employment: Lynn stayed at Berkeley for another year before hitting the job market because she was “always interested in individual differences, and always believed that testing college students only was a serious mistake.” She did a postdoc in developmental psychology to broaden her research experience.

Her first job was at Carlton University in Ottawa, Canada, where she encountered “rampant sexism” as well as racism—by English speakers against French speakers.” In addition, there was much anti-American sentiment because of the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam war. “It was a very uncomfortable year.”

Research: Throughout her long career, Lynn has published over 200 empirical articles on attentional processes and how they affect other cognitive abilities, such as memory and language. She has also studied these effects in the elderly and across cultures. A few of her lines of research are highlighted here.

In 1977 Lynn published research with her spouse, David Goldstein, and colleague Thomas Toppino, on what’s now called the illusory truth effect. “The idea was that knowledge accumulates automatically via fundamental building blocks such as frequency, rather than mere associations.” They found that peoples’ ratings of the veracity of a list of statements were influenced by prior exposure to the statements, regardless of statement accuracy. In other words, the more we hear a fact—regardless of whether it’s true or not—the more likely we will perceive it as true. Lynn and colleagues were so concerned about the potential misuse of the findings outside academia that they intentionally gave the article an ambiguous title: “Frequency and the conference of referential validity.” Ten years or so later, another research group replicated the findings, and more studies ensued. The phenomenon was eventually renamed the illusory truth effect.