Visiting Poets

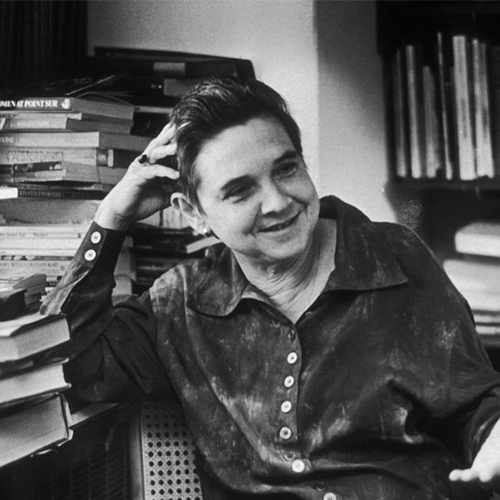

Adrienne Rich

Adrienne Rich‘s life and writings have bravely and eloquently challenged roles, myths, and assumptions for half a century. She has been a fervent activist against racism, sexism, economic injustice, and homophobia. Her exacting and provocative work is required reading in English and Women’s Studies courses throughout the U.S.

Rich has authored more than fifteen volumes of poetry and four books of non-fiction prose, most recently Fox and Arts of the Possible: Essays and Conversations. Beginning with the Yale Series of Younger Poets prize, awarded to her at age twenty-two for A Change of World, she has received countless literary honors, including the prestigious Tanning Award for Mastery in the Art of Poetry, an Academy of Poetry Fellowship, the Ruth Lilly Prize, the Common Wealth Award in Literature, two Guggenheims, the MacArthur Fellowship, the Lannan Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, and the National Book Award, which she accepted with Audre Lorde and Alice Walker on behalf of all women who are silenced.

For Rich, activism and art are inexorably intertwined. “Poetry,” she writes, “can remind us of all we are in danger of losing – disturb us, embolden us out of our resignation.” While her search for social justice has informed her life and her work, the poems, rather than suffering under the yoke of a heavy ideology, are brilliantly varied in their strategies and capacities to disturb and empower. As Poet David Wagoner’s 1996 citation proclaimed: “At every stage of her development, she has not simply pleased her admirers, but has surprised them. Her ingenuity in structure and diction, the variety and intensity of her forms and voices, and the emotional depth they have enabled her to reach…have made her lifetime of work a demonstration of what the Tanning Prize was meant to reward: mastery.”

The one prize Rich chose to decline was the National Medal for the Arts, awarded in 1997 by the National Endowment for the Arts and President Clinton. “I could not accept such an award from President Clinton or this White House,” she wrote in a letter to the New York Times, “because the very meaning of art, as I understand it, is incompatible with the cynical politics of this administration. [A]rt means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner-table of power which holds it hostage. The radical disparities of wealth and power in America are widening at a devastating rate. A President cannot meaningfully honor certain token artists while the people at large are so dishonored.”

Rich’s commitment to a ruthless examination of the self, as well as of society, has produced a body of work that traces her transformation from the well-behaved wife and formalist of the early poems to the fierce and politically artful writer she became. A partial, chronological listing of book titles (poetry and prose) provides an abbreviated narrative of this process and its concerns: Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law, Necessities of Life, The Will to Change, Diving into the Wreck, The Dream of a Common Language, On Lies, Secrets and Silence, A Wild Patience Has Taken Me This Far, Time’s Power, An Atlas of the Difficult World, Dark Fields of the Republic, Midnight Salvage, Arts of the Possible.

Rich’s work is living, necessary proof of the need for and the possibility of union between art and politics. As the late June Jordan put it, she “inflames our otherwise withering moral consciousness with tender and engendering inventions of language.” In the words of poet W. S. Merwin, “Adrienne Rich’s poems, volume after volume, have been the makings of one of the authentic, unpredictable, urgent, essential voices of our time.”

Adrienne Rich’s visit to Smith honors Carol T. Christ

upon her inauguration as the college’s tenth president.

Select Poems

You show me the poems of some woman

my age, or younger

translated from your language

Certain words occur: enemy, oven, sorrow

enough to let me know

she’s a woman of my time

obsessed

with Love, our subject:

we’ve trained it like ivy to our walls

baked it like bread in our ovens

worn it like lead on our ankles

watched it through binoculars as if

it were a helicopter

bringing food to our famine

or the satellite

of a hostile power

I begin to see that woman

doing things: stirring rice

ironing a skirt

typing a manuscript till dawn

trying to make a call

from a phonebooth

The phone rings unanswered

in a man’s bedroom

she hears him telling someone else

Never mind. She’ll get tired.

hears him telling her story to her sister

who becomes her enemy

and will in her own time

light her own way to sorrow

ignorant of the fact this way of grief

is shared, unnecessary

and political

1972

From DIVING INTO THE WRECK (Norton, 1973)

Should I simplify my life for you?

Don’t ask me how I began to love men.

Don’t ask me how I began to love women.

Remember the forties songs, the slowdance numbers

the small sex-filled gas-rationed Chevrolet?

Remember walking in the snow and who was gay?

Cigarette smoke of the movies, silver-and-gray

profiles, dreaming the dreams of he-and-she

breathing the dissolution of the wisping silver plume?

Dreaming that dream we leaned applying lipstick

by the gravestone’s mirror when we found ourselves

playing in the cemetery. In Current Events she said

the war in Europe is over, the Allies

and she wore no lipstick have won the war

and we raced screaming out of Sixth Period.

Dreaming that dream

we had to maze our ways through a wood

where lips were knives breasts razors and I hid

in the cage of my mind scribbling

this map stops where it all begins

into a red-and-black notebook.

Remember after the war when peace came down

as plenty for some and they said we were saved

in an eternal present and we knew the world could end?

-remember after the war when peace rained down

on the winds from Hiroshima Nagasaki Utah Nevada?

and the socialist queer Christian teacher jumps from the

hotel window?

and L.G. saying I want to sleep with you but not for sex

and the red-and-black enameled coffee-pot dripped slow through

the dark grounds

-appetite terror power tenderness

the long kiss in the stairwell the switch thrown

on two Jewish Communists married to each other

the definitive crunch of glass at the end of the wedding?

(When shall we learn, what should be clear as day,

We cannot choose what we are free to love?)

1993-1994

From DARK FIELDS OF THE REPUBLIC (Norton, 1995)

The engineer’s story of hauling coal

to Davenport for the cement factory, sitting on the bluffs

between runs looking for whales, hauling concrete

back to Gilroy, he and his wife renewing vows

in the glass chapel in Arkansas after 25 years

The flight attendant’s story murmured

to the flight steward in the dark galley

of her fifth-month loss of nerve

about carrying the baby she’d seen on the screen

The story of the forensic medical team’s

small plane landing on an Alaska icefield

of the body in the bag they had to drag

over the ice like the whole life of that body

The story of the man driving

600 miles to be with a friend in another country pp seeming

easy when leaving but afterward

writing in a letter difficult truths

Of the friend watching him leave remembering

the story of her body

with his once and the stories of their children

made with other people and how his mind went on

pressing hers like a body

There is the story of the mind’s

temperature neither cold nor celibate

Ardent The story of

not one thing only.

From THE SCHOOL AMONG THE RUINS (Norton, 2004)

I needed fox Badly I needed

a vixen for the long time none had come near me

I needed recognition from a

triangulated face burnt-yellow eyes

fronting the long body the fierce and sacrificial tail

I needed history of fox briars of legend it was said she

had run through

I was in want of fox

And the truth of briars she had to have run through

I craved to feel on her pelt if my hands could even slide

past her body slide between them sharp truth distressing

surfaces of fur

lacerated skin calling legend to account

a vixen’s courage in vixen terms

For a human animal to call for help

on another animal

is the most riven the most revolted cry on earth

come a long way down

Go back far enough it means tearing and torn endless

and sudden

back far enough it blurts

into the birth-yell of the yet-to-be human child

pushed out of a female the yet-to-be woman

1998

Available as a Broadside.Poetry Center Reading

Fall 2002Spring 2006