Visiting Poets

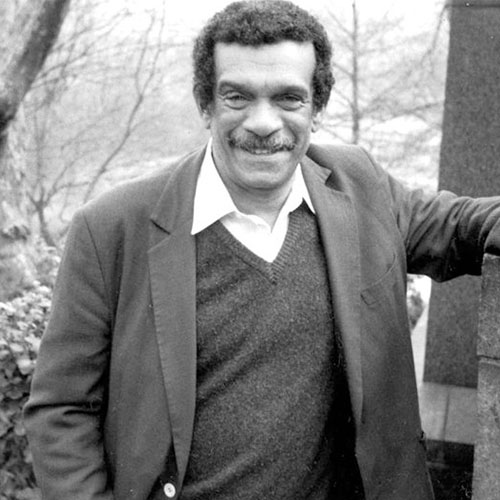

Derek Walcott

Derek Walcott won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1992, bringing Caribbean literature to international attention. Born in St. Lucia, West Indies, of Black, Dutch, and English descent, he grew up speaking Creole patois at home and learning English in school. Author of dozens of books – poems, essays, plays – Walcott has garnered countless honors, including a MacArthur “genius” grant. He has transformed the imperial English of the West Indies into what poet Alison Hawthorne Deming calls “a new way of singing.”

Walcott’s interest in drama dates back to his college days. After graduating from the University of the West Indies, he was awarded a fellowship by the Rockefeller Foundation to study the American theater, after which he returned to the Caribbean to found the Trinidad Theater Workshop, which produced many of his early plays. He went on to win an Obie Award for Dream on Monkey Mountain, and his poetic dramas have been produced by the New York Shakespeare Festival, the Mark Taper Forum, and the Negro Ensemble Company.

But Walcott is best known for his lush and incantatory verse. He has been incorporating Shakespearean and Biblical beauty with rich Caribbean rhythms for four decades, from the first collection, Green Night, to the recent Tiepolo’s Hound. Walcott’s epic poem Omeros weaves classical Greek, African, English, and Island traditions into a new kind of origin myth. Unafraid of majestic, he also plumbs the particular, exploring cultural divisions of language and race, as well as issues of isolation and estrangement. “Either I’m a nobody, or I’m a nation,” he writes, speaking to the personal and the historical at once. As author Pico Iyer suggested in Time magazine, “there is no more serious, or more sonorous, writer living.”

Walcott is also an accomplished painter. He teaches at Boston University, but still calls St. Lucia home.

Select Poems

A wind is ruffling the tawny pelt

Of Africa, Kikuyu, quick as flies,

Batten upon the bloodstreams of the veldt.

Corpses are scattered through a paradise.

Only the worm, colonel of carrion, cries:

“Waste no compassion on these separate dead!”

Statistics justify and scholars seize

The salients of colonial policy.

What is that to the white child hacked in bed?

To savages, expendable as Jews?

Threshed out by beaters, the long rushes break

In a white dust of ibises whose cries

Have wheeled since civilization’s dawn

From the parched river or beast-teeming plain.

The violence of beast on beast is read

As natural law, but upright man

Seeks his divinity by inflicting pain.

Delirious as these worried beasts, his wars

Dance to the tightened carcass of a drum,

While he calls courage still that native dread

Of the white peace contracted by the dead.

Again brutish necessity wipes its hands

Upon the napkin of a dirty cause, again

A waste of our compassion, as with Spain,

The gorilla wrestles with the superman.

I who am poisoned with the blood of both,

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the English tongue I love?

Betray them both, or give back what they give?

How can I face such slaughter and be cool?

How can I turn from Africa and live?

From IN A GREEN NIGHT (Jonathan Cape, 1962)

The time will come

when, with elation,

you will greet yourself arriving

at your own door, in your own mirror,

and each will smile at the other’s welcome,

and say, sit here. Eat.

You will love again the stranger who was your self.

Give win. Give bread. Give back your heart

to itself, to the stranger who has loved you

all your life, whom you ignored

for another, who knows you by heart.

Take down the love letters from the bookshelf,

the photographs, the desperate notes,

peel your own image from the mirror.

Sit. Feast on your life.

From SEA GRAPES (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1976)

(For Stephen Spender)

Somewhere a white horse gallops with its mane

plunging round a field whose sticks

are ringed with barbed wire, and men

break stones or bind straw into ricks.

Somewhere women tire of the shawled sea’s

weeping, for the fishermen’s dories

still go out. It is blue as peace.

Somewhere they’re tired of torture stories.

That somewhere there was an arrest.

Somewhere there was a small harvest

of bodies in the truck.Soldiers rest

somewhere by a road, or smoke in a forest.

Somewhere there is the conference rage

at an outrage.Somewhere a page

is torn out, and somehow the foliage

no longer looks like leaves but camouflage.

Somewhere there is a comrade,

a writer lying with his eyes wide open

on mattress ticking, who will not read

this, or write. How to make a pen?

And here we are free for a while, but

elsewhere, in one-third, or one-seventh

of this planet, a summary rifle butt

breaks a skull into the idea of a heaven

where nothing is free, where blue air

is paper-frail, and whatever we write

will be stamped twice, a blue letter,

its throat slit by the paper knife of the state.

Through these black bars

hollowed faces stare. Fingers

grip the cross bars of these stanzas

and it is here, because somewhere else

their stares fog into oblivion

thinly, like the faceless numbers

that bewilder you in your telephone

diary. Like last year’s massacres.

The world is blameless. The darker crime

is to make a career of conscience,

to feel through our own nerves the silent scream

of winter branches, wonders read as signs.

From THE ARKANSAS TESTAMENT (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1987)