Visiting Poets

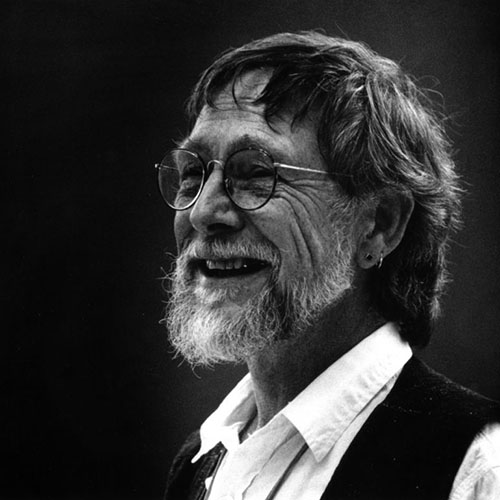

Gary Snyder

Gary Snyder has said, “I hold the most archaic values on earth,” extending even to the Paleolithic. His work is informed by his studies in Zen Buddhism and Asian languages, as well as a deep, earned knowledge of the natural world. While living in Japan for 12 years, he worked as a translator of Zen texts, also traveling and writing prolifically, working to see past the ignorance and unbalance prevalent in our dealings with the life around us and to divine the true nature of his subjects rather than give them his own meanings. His words ring and resonate with an understanding of the things around him, revealing to the reader truths which seem to have been evident all along.

In his first volume, Riprap, published in 1959, Snyder describes his works: “These poems, people,/lost ponies with/Dragging saddles/and rocky sure-foot trails.” The poet creates a verbal riprap, rock path by which we may cross with him the infinite terrains of ecology and human experience. His career, as Glyn Maxwell noted, “has been a remarkable combination of the academic and the contemplative, spiritual study and physical labor.” Snyder has been likened by some to a modern-day Henry David Thoreau, and the poet Edward Hirsch has called him “the most intimate and mindful of poets.”

Snyder’s honors include many for poetry, as well as for ecological literature. He has been awarded the Bollingen Poetry Prize, the Orion Society’s John Hay Award for Nature Writing, and a Pulitzer Prize for Turtle Island in 1975. He was also the first American literary figure to receive the Buddhist Transmission Award, for distinctive contributions in linking Zen thought and respect for the natural world across a lifelong body of poetry and prose. Snyder currently teaches at the University of California at Davis, where he lectures on literature and ecology.

Select Poems

Lay down these words

Before your mind like rocks.

placed solid, by hands

In choice of place, set

Before the body of the mind

in space and time:

Solidity of bark, leaf, or wall

riprap of things:

Cobble of milky way,

straying planets,

These poems, people,

lost ponies with

Dragging saddles

and rocky sure-foot trails.

The worlds like an endless

four-dimensional

Game of Go.

ants and pebbles

In the thin loam, each rock a word

a creek-washed stone

Granite: ingrained

with torment of fire and weight

Crystal and sediment linked hot

all change, in thoughts,

As well as things.

From THE GARY SNYDER READER (Counterpoint, 1999)

“The 1.5 billion cubic kilometers of water on the earth are split

by photosynthesis and

reconstituted once every two million years or so.”

A day on the ragged North Pacific coast get soaked by whipping mist,

rainsqualls tumbling, mountain mirror ponds, snowfield slush, rock-

wash creeks, earfuls of falls, sworls of ridge-edge snowflakes, swift grav-

elly rivers, tidewater crumbly glaciers, high hanging glaciers, shore-side

mud pools, icebergs, streams looping through the tideflats, spume of

brine, distant soft rain drooping from a cloud,

sea lions lazing under the surface of the sea-

We wash our bowls in this water

It has the flavor of ambrosial dew-

.

Beaching the raft, stagger out and shake off wetness like a

bear,

stand on the sandbar, rest from the river being

upwellings, sideswirls, backswirls

curl-overs, outripples, eddies, chops and swells

wash-overs, shallows confluence turbulence wash-seam

wavelets, riffles, saying

“A hydraulic’s a cross between a wave and a hole,

-you get a weir effect.

Pillow-rock’s total fold-back over a hole,

it shows spit on the top of the wave

a haystack’s a series of waves at the bottom of a tight

channel

there’s a tongue of the rapids — the slick tongue — the

‘v’—

some holes are ‘keepers,’ they won’t let you through;

eddies, backflows, we say ‘eddies are your friends.’

Current differential, it can suck you down

vertical boils are straight-up eddies spinning,

herringbone waves curl under and come back.

Well, let’s get going, get back to the rafts.”

Swing the big oars,

head into a storm.

We offer it to all demons and spirits

May all be filled and satisfied.

Om macula sai svaha!

.

Su Tung-p’o sat out one whole night by a creek on the slopes of Mt. Lu.

Next morning he showed this poem to his teacher:

The stream with its sounds is a long broad tongue

The looming mountain is a wide-awake body

Throughout the night song after song.

How can I speak at dawn.

Old master Chang-tsung approved him. Two centuries later Dogen said,

“Sounds of streams and shapes of mountains.

The sounds never stop and the shapes never cease.

Was it Su who woke

or was it the mountains and streams?

Billions of beings see the morning star

and all become Buddhas!

If you, who are valley streams and looming

mountains,

can’t throw some light on the nature of ridges and rivers,

who can?”

From MOUNTAINS AND RIVERS WITHOUT END (Counterpoint, 1996)

Eating the living germs of grasses

Eating the ova of large birds

the fleshy sweetness packed

around the sperm of swaying trees

The muscles of the flanks and thighs of

soft-voiced cows

the bounce in the lamb’s leap

the swish in the ox’s tail

Eating roots grown swoll

inside the soil

Drawing on life of living

clustered points of light spun

out of space

hidden in the grape.

Eating each other’s seed

eating

ah, each other.

Kissing the lover in the mouth of bread:

lip to lip.

From REGARDING WAVE (New Directions, 1970)

Available as a Broadside.