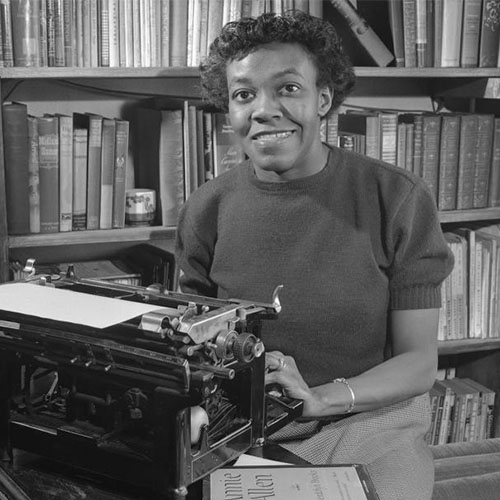

Visiting Poets

Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks has been a leading force in American letters for decades. Her poetry, writes Adrienne Rich, “holds up a mirror to the American experience entire, its dreams, self-delusions and nightmares. Her voice is inimitable.”

Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1917, she was the first Black writer to win the Pulitzer Prize (1950 for Annie Allen). Author of more than twenty books of poetry and recipient of many honors, including the Frost Medal and the Academy of American Poets’ Fellowship for distinguished poetic achievement, Brooks was writer-in-residence at Chicago State University and from 1968 until her death in 2000 served as the Poet Laureate of Illinois.

Select Poems

From the first it had been like a

Ballad. It had the beat inevitable. It had the blood.

A wildness cut up, and tied in little bunches,

Like the four-line stanzas of the ballads she had never quite

Understood-the ballads they had set her to, in school.

Herself: the milk-white maid, the “maid mild”

Of the ballad. Pursued

By the Dark Villain. Rescued by the Fine Prince.

The Happiness-Ever-After.

That was worth anything.

It was good to be a “maid mild.”

That made the breath go fast.

Her bacon burned. She

Hastened to hide it in the step-on can, and

Drew more strips from the meat case. The eggs and sour-milk biscuits

Did well. She set out a jar

Of her new quince preserve.

…But there was a something about the matter of the Dark Villian.

He should have been older, perhaps.

The hacking down of a villain was more fun to think about

When his menace possessed undisputed breadth, undisputed height,

And a harsh kind of vice.

And best of all, when his history was cluttered

With the bones of many eaten knights and princesses.

The fun was disturbed, then all but nullified

When the Dark Villain was a blackish child

Of fourteen, with eyes still too young to be dirty,

And a mouth too young to have lost every reminder

Of its infant softness.

That boy must have been surprised! For

These were grown-ups. Grown-ups were supposed to be wise.

And the Fine Prince-and that other-so tall, so broad, so

Grown! Perhaps the boy had never guessed

That the trouble with grown-ups was that under the magnificent shell of adulthood, just under,

Waited the baby full of tantrums.

It occurred to her that there may have been something

Ridiculous in the picture of the Fine Prince

Rushing (rich with the breadth and height and

Mature solidness whose lack, in the Dark Villain, was impressing her,

Confronting her more and more as this first day after the trial

And acquittal wore on) rushing

With his heavy companion to hack down (unhorsed)

That little foe.

So much had happened, she could not remember now what that foe had done

Against her, or if anything had been done.

The one thing in the world that she did know and knew

With terrifying clarity was that her composition

Had disintegrated. That, although the pattern prevailed,

The breaks were everywhere. That she could think

Of no thread capable of the necessary

Sew-work.

She made the babies sit in their places at the table.

Then, before calling Him, she hurried

To the mirror with her comb and lipstick. It was necessary

To be more beautiful than ever.

The beautiful wife.

For sometimes she fancied he looked at her as though

Measuring her. As if he considered, Had she been worth It?

Had she been worth the blood, the cramped cries, the little stuttering bravado,

The gradual dulling of those Negro eyes,

The sudden, overwhelming little-boyness in that barn?

Whatever she might feel or half-feel, the lipstick necessity was something apart. He must never conclude

That she had not been worth It.

He sat down, the Fine Prince, and

Began buttering a biscuit. He looked at his hands.

He twisted in his chair, he scratched his nose.

He glanced again, almost secretly, at his hands.

More papers were in from the North, he mumbled. More meddling headlines.

With their pepper-words, “bestiality,” and “barbarism,” and

“Shocking.”

The half-sneers he had mastered for the trial worked across

His sweet and pretty face.

What he’d like to do, he explained, was kill them all.

The time lost. The unwanted fame.

Still, it had been fun to show those intruders

A thing or two. To show that snappy-eyed mother,

That sassy, Northern, brown-black-

Nothing could stop Mississippi.

He knew that. Big Fella

Knew that.

And, what was so good, Mississippi knew that.

Nothing and nothing could stop Mississippi.

They could send in their petitions, and scar

Their newspapers with bleeding headlines. Their governors

Could appeal to Washington…

“What I want,” the older baby said, “is ‘lasses on my jam.”

Whereupon the younger baby

Picked up the molasses pitcher and threw

The molasses in his brother’s face. Instantly

The Fine Prince leaned across the table and slapped

The small and smiling criminal.

She did not speak. When the Hand

Came down and away, and she could look at her child,

At her baby-child,

She could think only of blood.

Surely her baby’s cheek

Had disappeared, and in its place, surely,

Hung a heaviness, a lengthening red, a red that had no end.

She shook her head. It was not true, of course.

It was not true at all. The

Child’s face was as always, the

Color of the paste in her paste-jar.

She left the table, to the tune of the children’s lamentations, which were shriller

Than ever. She

Looked out of a window. She said not a word. That

Was one of the new Somethings-

The fear,

Tying her as with iron.

Suddenly she felt his hands upon her. He had followed her

To the window. The children were whimpering now.

Such bits of tots. And she, their mother,

Could not protect them. She looked at her shoulders, still

Gripped in the claim of his hands. She tried, but could not resist the idea

That a red ooze was seeping, spreading darkly, thickly, slowly,

Over her white shoulders, her own shoulders,

And over all of Earth and Mars.

He whispered something to her, did the Fine Prince, something about love, something about love and night and intention.

She heard no hoof-beat of the horse and saw no flash of the shining steel.

He pulled her face around to meet

His, and there it was, close close,

For the first time in all those days and nights.

His mouth, wet and red,

So very, very, very red,

Closed over hers.

Then a sickness heaved within her. The courtroom Coca-Cola,

The courtroom beer and hate and sweat and drone,

Pushed like a wall against her. She wanted to bear it.

But his mouth would not go away and neither would the

Decapitated exclamation points in that Other Woman’s eyes.

She did not scream.

She stood there.

But a hatred for him burst into glorious flower,

And its perfume enclasped them-big,

Bigger than all magnolias.

The last bleak news of the ballad.

The rest of the rugged music.

The last quatrain.

From THE BEAN EATERS (Harper & Row, 1960)

1

People who have no children can be hard:

Attain a mail of ice and insolence:

Need not pause in the fire, and in no sense

Hesitate in the hurricane to guard.

And when wide world is bitten and bewarred

They perish purely, waving their spirits hence

Without a trace of grace or of offense

To laugh or fail, diffident, wonder-starred.

While through a throttling dark we others hear

The little lifting helplessness, the queer

Whimper-whine; whose unridiculous

Lost softness softly makes a trap for us.

And makes a curse. And makes a sugar of

The malocclusions, the inconditions of love.

2

What shall I give my children? who are poor,

Who are adjudged the leastwise of the land,

Who are my sweetest lepers, who demand

No velvet and no velvety velour;

But who have begged me for a brisk contour,

Crying that they are quasi, contraband

Because unfinished, graven by a hand

Less than angelic, admirable or sure.

My hand is stuffed with mode, design, device.

But I lack access to my proper stone.

And plentitude of plan shall not suffice

Nor grief nor love shall be enough alone

To ratify my little halves who bear

Across an autumn freezing everywhere.

3

And shall I prime my children, pray, to pray?

Mites, come invade most frugal vestibules

Spectered with crusts of penitents’ renewals

And all hysterics arrogant for a day.

Instruct yourselves here is no devil to pay.

Children, confine your lights in jellied rules;

Resemble graves; be metaphysical mules;

Learn Lord will not distort nor leave the fray.

Behind the scurryings of your neat motif

I shall wait, if you wish: revise the psalm

If that should frighten you: sew up belief

If that should tear: turn, singularly calm

At forehead and at fingers rather wise,

Holding the bandage ready for your eyes.

4

First fight. Then fiddle. Ply the slipping string

With feathery sorcery; muzzle the note

With hurting love; the music that they wrote

Bewitch, bewilder. Qualify to sing

Threadwise. Devise no salt, no hempen thing

For the dear instrument to bear. Devote

The bow to silks and honey. Be remote

A while from malice and from murdering.

But first to arms, to armor. Carry hate

In front of you and harmony behind.

Be deaf to music and to beauty blind.

Win war. Rise bloody, maybe not too late

For having first to civilize a space

Wherein to play your violin with grace.

5

When my dears die, the festival-colored brightness

That is their motion and mild repartee

Enchanted, a macabre mockery

Charming the rainbow radiance into tightness

And into a remarkable politeness

That is not kind and does not want to be,

May not they in the crisp encounter see

Something to recognize and read as rightness?

I say they may, so granitely discreet,

The little crooked questionings inbound,

Concede themselves on most familiar ground,

Cold an old predicament of the breath:

Adroit, the shapely prefaces complete,

Accept the university of death.

Part I of “The Womanhood” From ANNIE ALLEN (Harper & Row, 1949)

Today I learned the coora flower

grows high in the mountains of Itty-go-luba Bésa.

Province Meechee.

Pop. 39.

Now I am coming home.

This, at least, is Real, and what I know.

It was restful, learning nothing necessary.

School is tiny vacation. At least you can sleep.

At least you can think of love or feeling your boy friend

against you

(which is not free from grief).

But now it’s Real Business.

I am Coming Home.

My mother will be screaming in an almost dirty dress.

The crack is gone. So a Man will be in the house.

I must watch myself.

I must not dare to sleep.

From CHILDREN COMING HOME (The David Company, 1991)