Visiting Poets

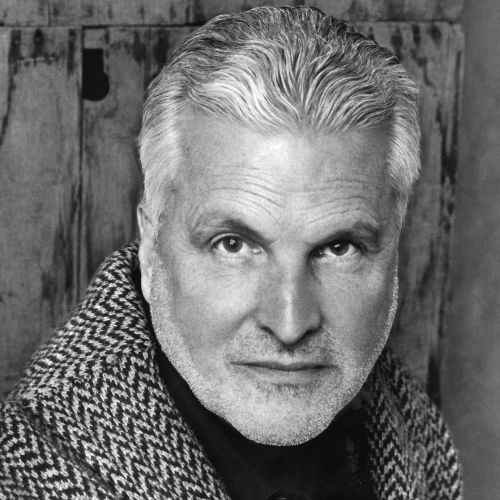

J.D. McClatchy

J.D. McClatchy’s contributions to American literary life are far-reaching. In addition to formally masterful poems – his fourth and most recent volume of poetry is Ten Commandments – he is known for elegant translations and poignant essays, including those collected in White Paper, which received the Poetry Society of America’s Melville Cane Award. McClatchy is the acclaimed editor of The Yale Reviewand over a dozen books, including Woman in White: Poems by Emily Dickinson, The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Poetry, and Horace’s The Art of Poetry. He has taught at Princeton, Yale, and Columbia Universities, and over the past decade has become an accomplished librettist. His Orpheus Descending, commissioned by the Chicago Lyric Opera for the Bruce Saylor production, premiered in 1994 and was subsequently broadcast on NPR’s “World of Opera.” McClatchy also contributed to Tobias Picker’s Emmeline, which was telecast on PBS’s “Great Performances”.

In 1996, McClatchy was named a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. Among his other honors, he has been awarded the Fellowship of the Academy of American Poets, the Award in Literature from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, and grants from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. Edmund White, of The Los Angeles Times Sunday Book Review, writes, “[A] poet such as McClatchy … reassure[s] us that the highest, most refining principles are still at play and that they have been applied, first and foremost, to his own poems, which are as new as they are old, as original as they are traditional.”

Select Poems

The sill is clammy to the touch, and the view familiar.

But doesn’t that moon seem a little too familiar?

His severed hand had been in someone’s pocket.

The stars hang perilously above Rue Familiar.

The whore’s pigeons seemed safe under his bowler,

But when he spotted an opening, the banker grew familiar.

His cloud saddle strapped to the sky’s flanks,

The Liberator arrived out of the blue. Familiar

Ideas, like glass shards, lay all over the floor,

Each with a part of the field pasted to familiar

Problems from the front page–the war, the scandals.

Men in uniform left us free to pursue familiar

Desires. But which came first, the cage or the egg?

What you dreamt was overdue, what you knew familiar.

Who owns the light? Who sold the sea its waves?

Perspective is the devil’s new familiar

If all property is theft, nothing’s left to give

The old man in Brussels but a few familiar

Imitations on cheap posters, enough to make seem

Strange what delicacies had been hitherto familiar.

Here is the pearl that made a grain of sand,

And the bricked-up alphabet that made you familiar.

From TEN COMMANDMENTS (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998)

If ever I did dream of such a matter,

Abhor me. And remember, I know my place.

In following him, I follow but myself.

All I want to do is help.

I’d rather have the tongue cut from my mouth

Than speak against my friend. This crack of love

Will grow stronger than it ever was before.

There’s reason to cool our raging, no?

I cannot think he means to do you any harm.

The chemotherapy seems promising.

These latest figures will show you what I mean.

All I want to do is help.

I had not thought he was acquainted with her.

Yes, yes, this boxcar is returning to Poland.

Sure, I’ve already tested negative twice.

I am bound to every act of duty.

Your sins are forgiven. This is only a phase.

I could swear it was her handkerchief I saw.

Trust me. Everything is under control.

All I want to do is help.

From TEN COMMANDMENTS (Alfred A. Knopf, 1998)

I.

In the shower, at the shaving mirror or beach,

For years I’d led…the unexamined life?

When all along and so easily within reach

(closer even than the nonexistent wife)

Lay the trouble–naturally enough

Lurking in a useless, overlooked

Mass of fat and old newspaper stuff

About matters I regularly mistook

As a horror story for the opposite sex,

Nothing to do with what at my downtown gym

Are furtively ogled as The Guy’s Pecs.

But one side is swollen, the too tender skin

Discolored. So the doctor orders an X-

Ray, and nervously frowns at my nervous grin.

II.

Mammography’s on the basement floor.

The nurse has an executioner’s gentle eyes.

I start to unbutton my shirt. She shuts the door.

Fifty, male, already embarrassed by the size

Of my “breasts,” I’m told to put the left one

Up on a smudged, cold, Plexiglas shelf,

Part of a robot half menacing, half glum,

Like a three-dimensional model of the Freudian self.

Angles are calculated. The computer beeps.

Saucers close on a flatness further compressed.

There’s an ache near the heart neither dull nor sharp.

The room gets lethal. Casually the nurse retreats

Behind her shield. Anxiety as blithely suggests

I joke about a snapshot for my Christmas Card.

III.

“No sign of cancer,” the radiologist swans

In to say–with just a hint in his tone

That he’s done me a personal favor__whereupon

His look darkens. “But what these pictures show…

Here, look, you’ll notice the gland on the left’s

Enlarged. See?” I see an aerial shot

Of Iraq, and nod. “We’ll need further tests,

Of course, but I’ll bet that what you’ve got

Is a liver problem. Trouble with your estrogen

Levels. It’s time, my friend, to take stock.

It happens more often than you’d think to men.”

Reeling from its millionth scotch on the rocks,

In other words, my liver’s sensed the end.

Why does it come a something less than a shock?

IV.

The end of life as I’ve known it, that is to say–

Testosterone sported like a power tie,

The matching set of drivers and dreads that may

Now soon be plumped to whatever new designs

My apparently resentful, androgynous

Inner life has on me. Blind seer?

The Bearded Lady in some provincial circus?

Something that others both desire and fear.

Still, doesn’t everyone long to be changed,

Transformed to, no matter, a higher of lower state,

To know the leather D-Day hero’s strange

Detachment, the queen bee’s dreamy loll?

Yes, but the future each of us blankly awaits

Was long ago written on the genetic wall.

V.

So suppose the breasts fill out until I look

Like my own mother…ready to nurse a son,

A version of myself, the infant understood

In the end as the way my own death had come.

Or will I in a decade be back here again,

The diagnosis this time not freakish but fatal?

The changed in one’s later years all tend,

Until the last one, toward the farcical,

Each of us slowly turned into something that hurts,

If soul is the final shape I shall assume.

(–A knock at the door. Time to button my shirt a

And head back out into the waiting room.)

Which of my bodies will have been the best disguise?

From TEN COMMANDMENTS(Alfred A. Knopf, 1998)