Visiting Poets

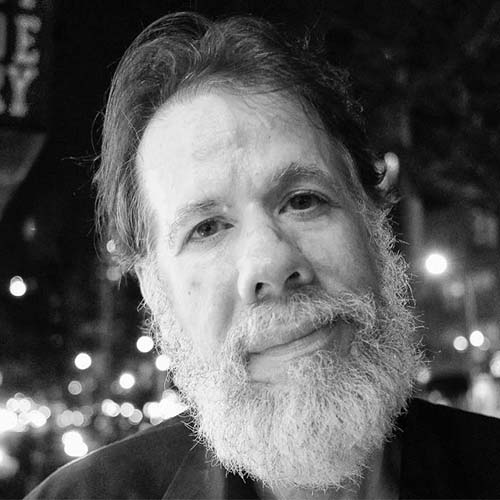

Martín Espada

Martín Espada is a rare creature: a successfully political poet. His work is often described as the poetry of advocacy; Espada speaks in the voices of those whose words and acts are so often ignored. John Bradley calls him “the true poet laureate of this nation.”

Espada was born and raised in Brooklyn, New York, by his Puerto Rican father and Jewish mother. His father, Frank Espada, was an important civil rights leader and Puerto Rican activist; Martín describes him as “the one-time leader of a million Puerto Ricans in New York City.” This invaluable influence led to Martín Espada’s activism. He studied history at the University of Wisconsin and received his law degree from Northeastern University Law School in 1985. He worked as a tenant lawyer in eastern Massachusetts until he was appointed professor of English at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

Espada’s six books of poetry have been widely honored. Rebellion Is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands won the PEN/Revson award and the Paterson Poetry Prize in 1989, and Imagine the Angels of Bread won the American Book Award in 1997. His most recent collection of poetry, A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen, was published to rave reviews in 2000. Yusef Komunyakaa writes, “A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen recalibrates history till a scary clarity stares us in the eyes. We cannot play ignorant as we face Espada’s music and imagery in these point-blank poems.” Russell Banks also praises Espada, declaring, “His ambition and his achievement remind us of Whitman, where it all begins.”

Espada is also an essayist, translator, and editor. He lives with his wife and son and teaches at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Select Poems

This was the first Thanksgiving with my wife’s family,

sitting at the stained pine table in the dining room.

The wood stove coughed during her mother’s prayer:

Amen and the gravy boat bobbing over fresh linen.

Her father stared into the mashed potatoes

and saw a white battleship floating in the gravy.

Still staring at the mashed potatoes, he began a soliloquy

about the new Navy missiles fired across miles of ocean,

how they could jump into the smokestack of a battleship.

“Now in Korea,” he said, “I was a gunner and the people there

ate kimch’i and it really stinks.” Mother complained that no one

was eating the creamed onions. “Eat, Daddy.” The creamed onions

look like eyeballs, I thought, and then said, “I wish I had missiles

like that.” Daddy laughed a 1950s horror-movie mad-scientist laugh,

and told me he didn’t have a missile, but he had his own cannon.

“Daddy, eat the candied yams,” Mother hissed, as if he were

a liquored CIA spy telling secrets about military hardware

to some Puerto Rican janitor he met in a bar. “I’m a toolmaker.

I made the cannon myself,” he announced, and left the table.

“Daddy’s family has been here in the Connecticut Valley since 1680,”

Mother said. “There were Indians here once, but they left.”

When I started dating her daughter, Mother called me a half-Black,

But now she spooned candied yams on my plate. I nibbled

at the candied yams. I remembered my own Thanksgivings

in the Bronx, turkey with arroz y habichuelas and plátanos,

and countless cousins swaying to bugalú on the record player

or roaring at my grandmother’s Spanish punch lines in the kitchen,

the glowing of her cigarette like a firefly lost in the city. For years

I thought everyone ate rice and beans with turkey at Thanksgiving.

Daddy returned to the table with a cannon, steering the black

steel barrel. “Does that cannon go boom?” I asked. “I fire it

in the backyard at the tombstones,” he said. “That cemetery bought

up all our farmland during the Depression. Now we only have

the house.” He stared and said nothing, then glanced up suddenly,

like a ghost had tickled his ear. “Want to see me fire it?” he grinned.

“Daddy, fire the cannon after dessert,” Mother said. “If I fire

the cannon, I have to take out the cannonballs first,” he told me.

He tilted the cannon downward, and cannonballs dropped

from the barrel, thudding on the floor and rolling across

the brown braided rug. Grandmother praised the turkey’s thighs,

said she would bring leftovers home to feed her Congo Gray parrot.

I walked with Daddy to the backyard, past the bullet holes

in the door and his pickup truck with the Confederate license plate.

He swiveled the cannon around to face the tombstones

on the other side of the backyard fence. “This way, if I hit anybody,

they’re already dead,” he declared. He stuffed half a charge

of gunpowder into the cannon, and lit the fuse. From the dining room,

Mother yelled, “Daddy, no!” Then the battlefield rumbled

under my feet. My head thundered. Smoke drifted over

the tombstones. Daddy laughed. And I thought: When the first

drunken Pilgrim dragged out the cannon at the first Thanksgiving-

that’s when the Indians left.

From A MAYAN ASTRONOMER IN HELL’S KITCHEN (W.W. Norton, 2000)

We were sitting in traffic

on the Brooklyn Bridge,

so I asked the poets

in the backseat of my cab

to write a poem for you.

They asked

if you are like the moon

or the trees.

I said no,

she is like the bridge

when there is so much traffic

I have time

to watch the boats

on the river.

From A MAYAN ASTRONOMER IN HELL’S KITCHEN (W.W. Norton, 2000)

More than the moment

when forty gringo vigilantes

cheered the rope

that snapped two Mexicanos

into the grimacing sleep of broken necks,

more than the floating corpses,

trussed like cousins of the slaughterhouse,

dangling in the bowed mute humility

of the condemned,

more than the Virgen de Guadalupe

who blesses the brownskinned

and the crucified,

or the guitar-plucking skeletons

they will become

on the Día de los Muertos,

remain the faces of the lynching party:

faded as pennies from 1877, a few stunned

in the blur of execution,

a high-collar boy smirking, some peering

from the shade of bowler hats, but all

crowding into the photograph.

From REBELLION IS THE CIRCLE OF A LOVER’S HANDS (Curbstone Press, 1990)

Poetry Center Reading

Fall 2001Fall 2003