Visiting Poets

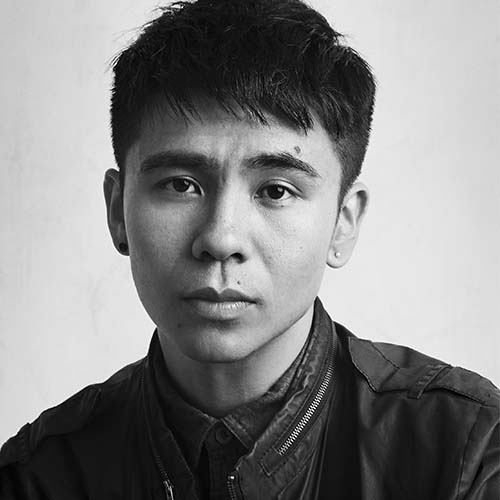

Ocean Vuong

Hailed by BuzzFeed Books as one of “32 Essential Asian American Writers,” Ocean Vuong is a biographer of violence, dislocation, and an immigrant, queer America that carries trauma from other lands, still breathing. Vuong’s debut collection, Night Sky with Exit Wounds (Copper Canyon, 2016), was named by the New York Timesas a Top 10 Book of 2016, and garnered a slew of honors: a Whiting Award, a Thom Gunn Award, the Lambda Literary Prize, finalist for Forward Prize for Best First Collection, and the Kate Tufts Discovery Award.

Vuong’s poems are whispered prayers of the body that seek a pathway out of trauma in intimacy. He was described by The New York Times as a poet who “captures specific moments in time with both photographic clarity and a sense of the evanescence of all earthly things,” whose work possesses “a tensile precision reminiscent of Emily Dickinson’s work, combined with a Gerard Manley Hopkins-like appreciation for the sound and rhythms of words. Vuong was born on a rice farm outside Saigon, and spent a year in a refugee camp in the Philippines before moving, at age two, to Hartford, CT. He was influenced by the Vietnamese oral poetic tradition he grew up with, and calls the ear “his first instrument,” as he internalized the stories and poems his family “carries… inside their bodies.” Reading his poems, writes Daniel Wenger of the New Yorker is like “watching a fish move” through the “currents of English with muscled intuition.”

The poems in Vuong’s blazing debut are searingly metaphysical in their treatment of time, the body, and identity, at once uncovering and resurfacing histories that are interwoven with the present. His Whiting Award citation notes how the poems “unflinchingly face the legacies of violence and cultural displacement but… also assume a position of wonder before the world.” Speaking to the way Vuong’s personal archaeological work with identity moves beyond one body and speaks to the seemingly private anxieties we share, Li-Young Lee describes the collection as “a gift. . .a perfume…crushed and rendered of his heart and soul.”

In addition to the Poetry Foundation’s Ruth Lilly Fellowship, Vuong is the recipient of fellowships from the Academy of American Poets, the Lannan Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, the Elizabeth George Foundation. His poems have been featured in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Nation, New Republic, The Village Voice, and American Poetry Review, which awarded him the Stanley Kunitz Prize for Younger Poets. He has also published two chapbooks, Burnings (2010) and No (2013). He was also selected by Foreign Policy magazine as a one of 2016’s 100 Leading Global Thinkers, alongside Hillary Clinton, Ban Ki-Moon and Warsan Shire. Vuong holds an MFA from New York University, and in 2016 left New York for the Northampton area. This fall he became an Assistant Professor in the MFA Program at UMass Amherst.

Select Poems

After Frank O’Hara / After Roger Reeves

Ocean, don’t be afraid.

The end of the road is so far ahead

it is already behind us.

Don’t worry. Your father is only your father

until one of you forgets. Like how the spine

won’t remember its wings

no matter how many times our knees

kiss the pavement. Ocean,

are you listening? The most beautiful part

of your body is wherever

your mother’s shadow falls.

Here’s the house with childhood

whittled down to a single red tripwire.

Don’t worry. Just call it horizon

& you’ll never reach it.

Here’s today. Jump. I promise it’s not

a lifeboat. Here’s the man

whose arms are wide enough to gather

your leaving. & here the moment,

just after the lights go out, when you can still see

the faint torch between his legs.

How you use it again & again

to find your own hands.

You asked for a second chance

& are given a mouth to empty into.

Don’t be afraid, the gunfire

is only the sound of people

trying to live a little longer. Ocean. Ocean,

get up. The most beautiful part of your body

is where it’s headed. & remember,

loneliness is still time spent

with the world. Here’s

the room with everyone in it.

Your dead friends passing

through you like wind

through a wind chime. Here’s a desk

with the gimp leg & a brick

to make it last. Yes, here’s a room

so warm & blood-close,

I swear, you will wake—

& mistake these walls

for skin.

From NIGHT SKY WITH EXIT WOUNDS (Copper Canyon Press, 2016)

you ride your bike to the park bruised

with 9pm the maples draped with plastic bags

shredded from days the cornfield

freshly razed & you’ve lied

about where you’re going you’re supposed

to be out with a woman you can’t find

a name for but he’s waiting

in the baseball field behind the dugout

flecked with newports torn condoms

he’s waiting with sticky palms & mint

on his breath a cheap haircut

& his sister’s levis

stench of piss rising from wet grass

it’s june after all & you’re young

until september he looks different

from his picture but it doesn’t matter

because you kissed your mother

on the cheek before coming

this far because the fly’s dark slit is enough

to speak through the zipper a thin scream

where you plant your mouth

to hear the sound of birds

hitting water snap of elastic

waistbands four hands quickening

into dozens: a swarm of want you wear

like a bridal veil but you don’t

deserve it: the boy

& his loneliness the boy who finds you

beautiful only because you’re not

a mirror because you don’t have

enough faces to abandon you’ve come

this far to be no one & it’s june

until morning you’re young until a pop song

plays in a dead kid’s room water spilling in

from every corner of summer & you want

to tell him it’s okay that the night is also a grave

we climb out of but he’s already fixing

his collar the cornfield a cruelty steaming

with manure you smear your neck with

lipstick you dress with shaky hands

you say thank you thank you thank you

because you haven’t learned the purpose

of forgive me because that’s what you say

when a stranger steps out of summer

& offers you another hour to live.

From NIGHT SKY WITH EXIT WOUNDS (Copper Canyon Press, 2016)

after Newtown, CT

I don’t know the name of the white mare

swaying in early light, her mane tinged blue

with rain, but my mouth has found

the warmest vein beneath

her jaw—and so what

if my bones were hammered

into the shape of a man’s

regret. I’m only here to increase

the silence, despite music. And it’s hard

to pray with just one word

in the chamber—but I try. Like you,

I try, willing as the hand that holds me.

Like you, I thought I heard the thunder

of a world coming to its end.

It was only the sound of hooves

running nowhere.

First published by the Paris-American, 2013