Visiting Poets

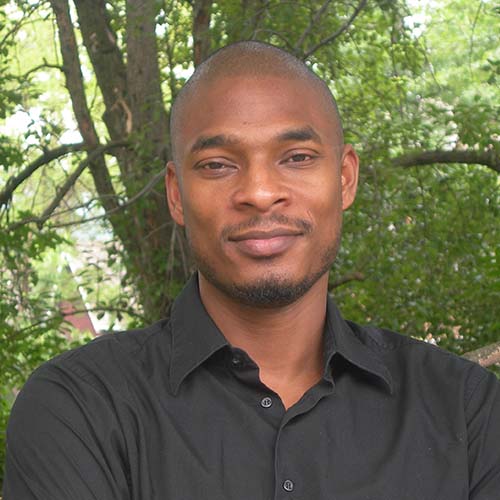

Terrance Hayes

The day after Trump’s election, Terrance Hayes wrote the first of the seventy sonnets that comprise his new collection, American Sonnets for My Past And Future Assassin (Penguin Books, 2018). In poems that are in turn elegiac, funny, solemn and vengeful, Hayes engages with American politics, racism, history and artistic heritage. "Our sermon/Today sets the beauty of sin against the purity of dirt," Hayes writes, inviting his readers to examine & dismantle conventional ways of generating meaning that have historically diminished or ignored voices of color. American Sonnets was a finalist for the 2018 National Book Award and was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry. Hayes, a MacArthur Fellow and the author of six books of poetry, is also the recipient of a National Book Award and a Guggenheim Fellowship, among numerous other honors. He is currently a Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, as well as a professor of English at New York University.

Select Poems

When I consider the much discussed dilemma

of the African-American, I think not of the diasporic

middle passing, unchained, juke, jock, and jiving

sons and daughters of what sleek dashikied poets

and tether fisted Nationalists commonly call Mother

Africa, but of an ex-girlfriend who was the child

of a black-skinned Ghanaian beauty and Jewish-

American, globetrotting ethnomusicologist.

I forgot all my father’s warnings about meeting women

at bus stops (which is the way he met my mother)

when I met her waiting for the rush hour bus in October

because I have always been a sucker for deep blue denim

and Afros and because she spoke so slowly

when she asked me the time. I wrote my phone number

in the back of the book of poems I had and said

something like “You can return it when I see you again”

which has to be one of my top two or three best

pickup lines ever. If you have ever gotten lucky

on a first date you can guess what followed: her smile

twizzling above a tight black v-neck sweater, chatter

on my velvet couch and then the two of us wearing nothing

but shoes. When I think of African-American rituals

of love, I think not of young, made-up unwed mothers

who seek warmth in the arms of any brother

with arms because they never knew their fathers

(though that could describe my mother), but of that girl

and me in the basement of her father’s four story Victorian

making love among the fresh blood and axe

and chicken feathers left after the Thanksgiving slaughter

executed by a 3-D witch doctor houseguest (his face

was starred by tribal markings) and her ruddy American

poppa while drums drummed upstairs from his hi-fi woofers

because that’s the closest I’ve ever come to anything

remotely ritualistic or African, for that matter.

We were quiet enough to hear their chatter

between the drums and the scraping of their chairs

at the table above us and the footsteps of anyone

approaching the basement door and it made

our business sweeter, though I’ll admit I wondered

if I’d be cursed for making love under her father’s nose

or if the witchdoctor would sense us and then cast a spell.

I have been cursed, broken hearted, stunned, frightened

and bewildered, but when I consider the African-American

I think not of the tek nines of my generation deployed

by madness or that we were assigned some lousy fate

when God prescribed job titles at the beginning of Time

or that we were too dumb to run the other way

when we saw the wide white sails of the ships

since given the absurd history of the world, everyone

is a descendant of slaves (which makes me wonder

if outrunning your captors is not the real meaning of Race?).

I think of the girl’s bark colored, bi-continental nipples

when I consider the African-American.

I think of a string of people connected to one another

and including the two of us there in the basement

linked by a hyphen filled with blood;

linked by a blood filled baton in one great historical relay.

From WIND IN A BOX (Penguin, 2006)

The song must be cultural, confessional, clear

But not obvious. It must be full of compassion

And crows bowing in a vulture’s shadow.

The song must have six sides to it & a clamor

Of voltas. The song must turn on the compass

Of language like a tangle of wire endowed

With feeling. The notes must tear & tear,

There must be a love for the minute & minute,

There must be a record of witness & daydream,

Where the heart is torn or feathered & tarred,

Where death is undone, time diminished,

The song must hold its own storm & drum,

And shed a noise so lovely it is sung at sunset

Weddings, baptisms & beheadings henceforth.

from AMERICAN SONNETS FOR MY PAST AND FUTURE ASSASSIN (Penguin, 2018)

I thought we might as well sing the fables of sea

To fill our mouths before sailing out to whale.

I thought we might sing as well of the feeling

Of sea moving about the whale like a coat.

The color of water is always the temperature

Of a mirror. I thought we might drown

Our reflections in a swaying like our songs

Of mother wit & mother woe, our toasts

With the water a deep dark blue, an almost

Indigo we paled from the well before sail.

Whale-road is a kenning for sea. Time-machine

Is a kenning for the mind. Alive is a kenning

For the electrified. I thought we might sing

Of the wire wound round the wound of feeling.

from AMERICAN SONNETS FOR MY PAST AND FUTURE ASSASSIN (Penguin, 2018)

Poetry Center Reading

Fall 2019Fall 2006