Visiting Poets

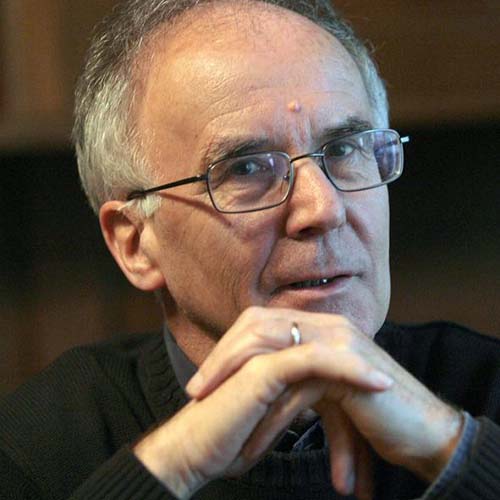

Tomaž Šalamun

Tomaž Šalamun was born in Zagreb, Croatia, raised in Koper, Slovenia, and now makes his home in Ljubljana. He studied art history and worked as a curator and a conceptual artist before turning to the written word. Having published 25 volumes of poems in his native Slovenia, Salamun has received many prizes in Europe and been translated into nearly a dozen languages.

The Selected Poems Of Tomaž Šalamun, edited and in large part translated by Charles Simic, was the poet’s debut collection in English, brought out in 1988 as part of Ecco Press’s prestigious Modern European Poetry series. It was followed by The Shepherd, The Hunter (1992), translated by Sonja Kravanja, and The Four Questions Of Melancholy (White Pine Press, 1997); this greatly expanded collection of some 200 poems was edited by Christopher Merrill, another of Salamun’s poet-translators. Feast, his fourth volume in English, is due out from Harcourt Brace this year.

Salamun has won exuberant praise from many American poets, including James Tate, Robert Creeley, Robert Hass, who celebrates his “love of the poetics of rebellion,” and Jorie Graham, who calls his work “one of Europe’s great philosophical wonders.”

Select Poems

I should’ve been born in Trieste in 1884

on the Acquedotto, but it didn’t turn out that way.

I remember the three-storied reddish house,

the ground floor with its furnished living room,

my great-grandfather (my father)

nervously studying the stock market reports,

blowing cigar smoke and calculating quickly.

When I was already for months inside my great-

grandmother, there was a family council,

the result of which was the postponement

of my arrival for two generations.

The decision was written down, the sheet stuffed

into an envelope, sealed and sent to an archive in Vienna.

I remember traveling back toward the light

on my belly, and watching an old man

fussing as he measured the shelf, taking another body from the shelf

and shoving it by the head down the air shaft.

I had the impression I was seven years old,

and that my substitute, my grandfather,

was a bit older, nine or ten.

I was composed. At the same time these events disturbed me.

I remember that for a time I withered,

most likely because of the strong light,

and then my lungs flattened like a bag.

When I reached the proper tonus I fell asleep.

I knew my body was down below,

and in my dream I saw it many times.

It was that of a slow-moving man with mustaches,

a dreamer and a banker his whole life.

From THE FOUR QUESTIONS OF MELANCHOLY (White Pine Press, 1997)

Tomaz Salamun is a monster.

Tomaz Salamun is a sphere rushing through the air.

He lies down in twilight, he swims in twilight.

People and I, we both look at him amazed,

we wish him well, maybe he is a comet.

Maybe he is punishment from the gods,

the boundary stone of the world.

Maybe he is such a speck in the universe

that he will give energy to the planet

when oil, steel, and food run short.

He might only be a hump, his head

should be taken off like a spider’s.

But then something would then suck up

Tomaz Salamun, possibly the head.

Possibly he should be pressed between

glass, his photo should be taken.

He should be put in formaldehyde, so children

would look at him as they do at fetuses,

protei, and mermaids.

Next year, he’ll probably be in Hawaii

or in Ljubljana. Doorkeepers will scalp

tickets. People will walk barefoot

to the university there. The waves can be

a hundred feet high. The city is fantastic,

shot through with people on the make,

the wind is mild.

But in Ljubljana people say: look!

This is Tomaz Salamun, he went to the store

with his wife Maruska to buy some milk.

He will drink it and this is history.

From THE FOUR QUESTIONS OF MELANCHOLY (White Pine Press, 1997)

Destiny rolls over me. Sometimes like an egg. Sometimes

with its paws, slamming me into the slope. I shout. I take

my stand. I pledge all my juices. I shouldn’t

do this. Destiny can snuff me out, I feel it now.

If destiny doesn’t blow on our souls, we freeze

instantly. I spent days and days afraid

the sun wouldn’t rise. That this was my last day.

I felt light sliding from my hands, and if I didn’t

have enough quarters in my pocket, and Metka’s voice

were not sweet enough and kind and

solid and real, my soul would escape from my body, as one day

it will. With death you have to be kind.

Home is where we’re from. Everything in a moist dumpling.

We live only for a flash. Until the lacquer dries.

From THE FOUR QUESTIONS OF MELANCHOLY (White Pine Press, 1997)