Carbon Neutral by 2030

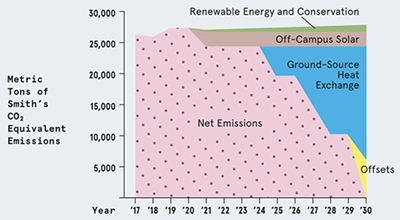

By decreasing its greenhouse gas emissions, reducing its energy consumption and cleaning up its energy supply with renewable sources such as solar and wind power, Smith is making good on its promise to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030.

Acting against climate change is a community-wide endeavor. Across campus, faculty, students and staff are investigating and testing innovative ideas around climate science, engineering, public health, policy and design—all in an effort to move the college—and the world—toward a clean, healthy and equitable energy future.

The Basics

Carbon neutrality: achieving net zero carbon emissions by sequestering or offsetting the equivalent amount of carbon or greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as we release.

Renewable energy sources: naturally-occurring and constantly replenished sources, such as sun and wind.

Transitioning the global economy from non-renewable sources, such as coal and natural gas, to renewable sources is critical for mitigating climate change.

Our Commitments

Smith joined Second Nature (The Climate Leadership Network) by signing the Carbon Commitment. In doing so, the college pledged to create a climate action plan that included a “target date for achieving carbon neutrality as soon as possible.” Smith’s Sustainability and Climate Action Management Plan (SCAMP), released in 2010, outlined various strategies and technologies to investigate to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030.

In 2015, President Kathleen McCartney formed a Study Group on Climate Change (SGCC), made up of staff, faculty, trustees, alums and students, tasked with facilitating a campuswide examination of how Smith could most effectively respond to the challenge of global climate change. The study group’s work culminated in 2017 with a set of recommendations and priorities for academic offerings, campus programming and operations.

In December 2020, President McCartney underscored Smith’s persisting commitment by joining the “All In” movement on climate action signed by thousands of institutions, states and countries.

Geothermal Energy

In summer 2022, Smith began work on an innovative geothermal campus energy project that will reduce the college’s carbon emissions by an eye-popping 90%, allowing the college to become carbon neutral by 2030.

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PROJECT GEOTHERMAL PROJECT TIMELINE

“It’s the largest capital project in Smith’s history,” says David DeSwert, vice president for finance and administration. “It will represent somewhere between 35% and 40% of our capital expenditures over the next 10 years.”

Beyond that, the work fully aligns with the college’s mission and vision. “We knew it was important for Smith to take action on this because we believe that what we do in our campus operations reflects our values and what we’re teaching our students in the classroom,” DeSwert says.

The geothermal energy project may be the most concrete evidence of Smith’s commitment to sustainability, but it’s just one of many ways Smith uses its resources to live up to its stated values, DeSwert says. “We’ve also taken actions in our endowment to divest from investments in fossil-fuel-specific [asset] managers,” he says. “We believe in taking a comprehensive approach to practice what we preach.”

Big Moves for Sustainability

Research, teaching and leadership at Smith—and the students who internalize these ideas and live them out beyond graduation—are designed to make waves in the fight against climate change.

In 2016, we completed the Smith College Campus Decarbonization Study. As a result, the college charted a course to convert the existing heating, cooling, and electricity system from fossil fuel gas to renewable electric sources.

Smith has conducted geological, engineering, and financial analyses to refine this plan. This work has been informed by student and faculty research on state and federal policies, renewable sources in the New England region, evolving science around renewable technologies, battery storage, and much more.

As of 2021, the college is in design and implementation of a new renewably-powered district energy system. The system will be implemented over the course of the next 9 years.

Testing the Ground for its Potential

To investigate the viability of geothermal heat exchange for our campus, a test borehole was drilled in the ground near the Field House to evaluate the soil, hydraulic characteristics, and thermal response under our campus. Then, a heat pump was installed in the Field House and connected to the borehole, which provided heating and cooling through ground-source heat exchange.

Fleet

The college has around 86 vehicles to support operations, academics, research, and student work. As of 2021, four of those were hybrid or all-electric vehicles. Faculty and student research such as Carbon Neutrality Should Not Be the End Goal: Lessons for Institutional Climate Action From U.S. Higher Education and Electrifying Landscape Management are guiding future fleet electrification strategies and goals.

Commuting

Smith, located in a fairly rural setting, is nearby a variety of alternative transportation options including bus, rideshare, and bikeshare programs. While the carbon emissions associated with commuting for students is almost non-existent because we are a residential college, over 90% of staff and faculty drive alone to and from work. We are evaluating our parking and alternative transport incentive programs to see how we can increase use of zero-emissions transportation.

Academic-related travel

In 2018, students Cara Dietz ‘18, Eliana Gevelber ‘18, and Gray Li ‘18, evaluated Smith’s purchasing records to estimate the carbon emissions associated with the supply chain of goods and services we purchase as a college, also known as Scope 3 emissions. Their research found that air travel by faculty, staff, and students, paid for by the college accounts for almost 20% of our Scope 3 carbon emissions. This does not account for student-funded travel associated with college. While Smith is not actively working to reduce college-funded travel, we will use the lessons learned within the pandemic about remote work and convening to encourage faculty and staff to pause and get creative before they fly.

Smith has been implementing strategies for reducing waste on campus for decades.

While recycling, composting and reusing materials has become the norm, several unique initiatives have taken shape recently.

LEARN MORE ABOUT NEW INITIATIVESIn the spring of 2018 the Committee on Sustainability selected $70 per MTCO2e as the internalized cost of carbon emissions, or proxy carbon price, to help guide major capital budget management and other decision-making processes at Smith College. In 2018, President Kathleen McCartney also signed the Higher Education Carbon Pricing Endorsement Initiative to demonstrate Smith College’s support for carbon pricing.

The adoption was informed by Breanna Parker's ’18 honors thesis called Designing a Proxy Carbon Price Strategy for Smith College, advised by Alex Barron (ES&P), Susan Sayre (Economics) and Dano Weisbord (Executive Director of Campus Sustainability and Campus Planning). Parker’s thesis won a national Campus Sustainability Research Award from the Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education in 2018. Parker's work also laid the foundation for a collaborative paper published in the peer reviewed journal Elementa.

Smith has seven solar arrays on it’s buildings: Ford Hall, the Indoor Track and Tennis (ITT) Facility, the Campus Center, McConnell Hall, 67 West Street (a Smith-owned apartment building), the Bechtel Environmental Classroom at the MacLeish Field Station, and the Center for Early Childhood Development.

Together, the systems on Ford Hall and the ITT facility produce about 550,000 kilowatt hours of electricity a year equaling roughly 2% of our campus electricity consumption.

Co-op Power Project

In Spring 2017, Smith College partnered with the Co-op Power's Community Solar team to develop a local solar financing model for local nonprofits. Under this structure, local investors with real estate interests invest in local nonprofit solar projects, helping to use the solar tax incentives and bring down the overall costs for nonprofits. Nonprofits don't qualify for those tax incentives on their own. This innovative model brings the cost savings of solar to the nonprofit community. Smith College was the first nonprofit to sign on through the pilot phase of this program.

Student Highlight:

Eleanor Adachi's '17 honor project "Designing a photovoltaic array for Smith College"

In 2018, Smith, Amherst, Bowdoin, Hampshire and Williams colleges formed a collaborative called the New England College Renewable Partnership (NECRP) that contracted for 46,000 megawatt hours per year of electricity created at a new solar power facility to be built in Farmington, Maine. This agreement is the first example of a collaborative purchase of solar energy in New England higher education, and one of the first such multi-college collaborations in the United States. Project details can be found on the website that Smith student Larissa Holland '20 developed as part of her special studies on the Farmington Solar Project.

The project supplies 28% of the campus electricity needs, all of our scope 2 emissions (purchased electricity), which are 10% of our total carbon emissions.

Smith has been committed to sourcing sustainable dining options for some time now. Seeking out local farms and using plant-based alternatives wherever possible are two such ways that have gained momentum in recent years. Even without removing specific items from the menu, Smith is on track to cut the consumption of red meat by 15% by 2024.

LEARN MORE ABOUT RECENT MEASURESRefrigerants make up less than 1% of Smith’s emissions profile. Emissions from refrigerant releases occur infrequently at Smith and happen during some maintenance processes and when there is equipment failure. As a practice the campus already tries to minimize these types of releases and moves to less harmful refrigerants, such as 410, when available during equipment replacements. We reclaim all refrigerants when equipment is decommissioned.

However, as we move toward a nearly all-electric campus with additional summer cooling to buildings, we may increase our use of refrigerants as we install more air-source heat pumps, also known as mini-splits.